- The Ground Wasn’t Made In A Minute

- Man, Who Was Here First?

- Oh Man, the Colonists are here!

- There’s More to Concord than Minute Man, Man!

- What About the Plants and Animals, Man?

- Man, Do You Want to Go to Minute Man National Historical Park Now?

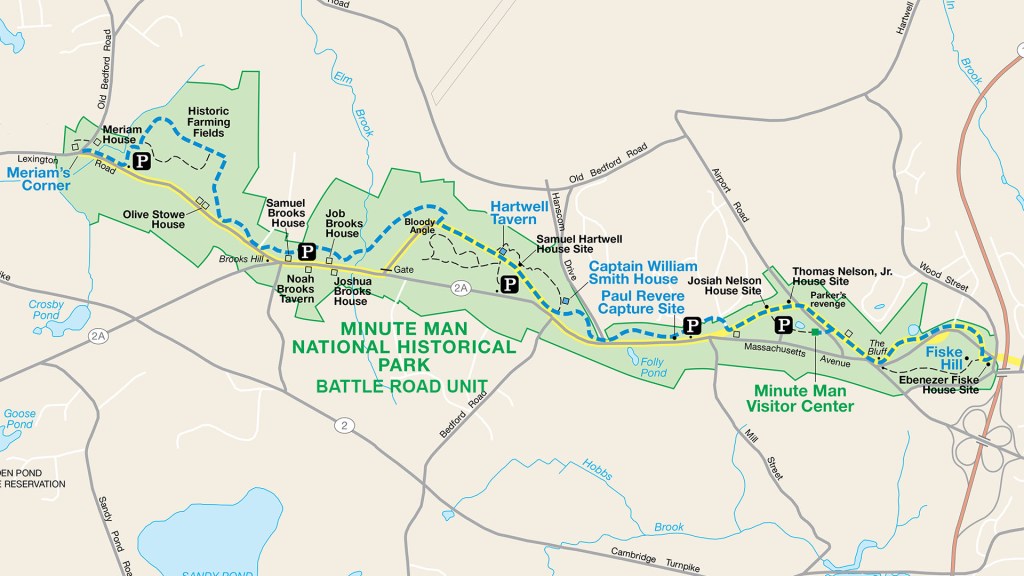

Minute Man National Historical Park is located in the towns of Lincoln, Concord, and Lexington, all Massachusetts. The site is famous for its role in the American Revolutionary War.

Courtesy of National Park Planner

The Ground Wasn’t Made In A Minute

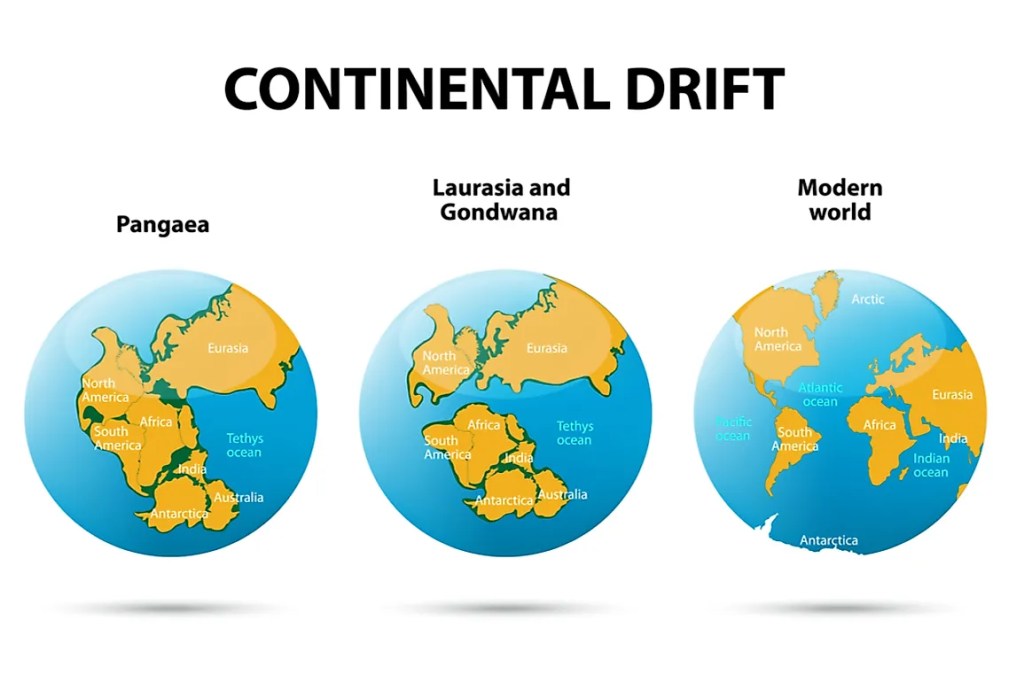

Minute Man is a result of more than the American Revolution, its soils have been subject to change for 600 million years. At one time, there were two continents in the world: Gondwana (which split into Africa, Australia, Antarctica, India, and South America) and Laurasia (which split into North America, Eurasia, and Greenland). Two volcanic chains were off Gondwana’s north coast, each with their own magma chambers.

Split of Pangea, Earth’s most famous mono-continental entity, into successive continents courtesy of World Atlas

The magma solidified into swathes of underground rock at the heart of the island chains – Avalon terrane the older chain, Nashoba terrane the younger chain. 500 million years ago, movement of the tectonic plates meant the Nashoba volcanic chain separated from Gondwana, moved towards the shores of Laurasia, and collided and sutured where North America is today. 20 million years after that, the Avalon terrane collided with the Nashoba terrane. The continent enlarged and acquired new mountains.

Bloody Bluff, a formation in Minute Man NHS, produced by terrane accretion (a process wherein island terranes smash into the edge of continents); the outcropping pictured is a segment of where the Nashoba and Avalon terranes fused – courtesy of National Park Service

The event, known as the Acadian orogeny, built the park’s bedrock. Over the next 75 million years, another continental collision occurred here, where North America and Africa collided (plus, Pangea’s breakup 200 million years ago). Since 200 million years ago, no tectonic activity has occurred beneath where Minute Man NHS is today. In the tectonic plates’ stead, wind, rain, and glaciers have formed the park’s features since. The glaciers in particular deserve mention: during the Pleistocene Era, or the last Ice Age, continental glaciers spread southward from the north pole to cover a third of North America.

North America’s Pleistocene glaciers at their greatest extent – courtesy of National Science Foundation

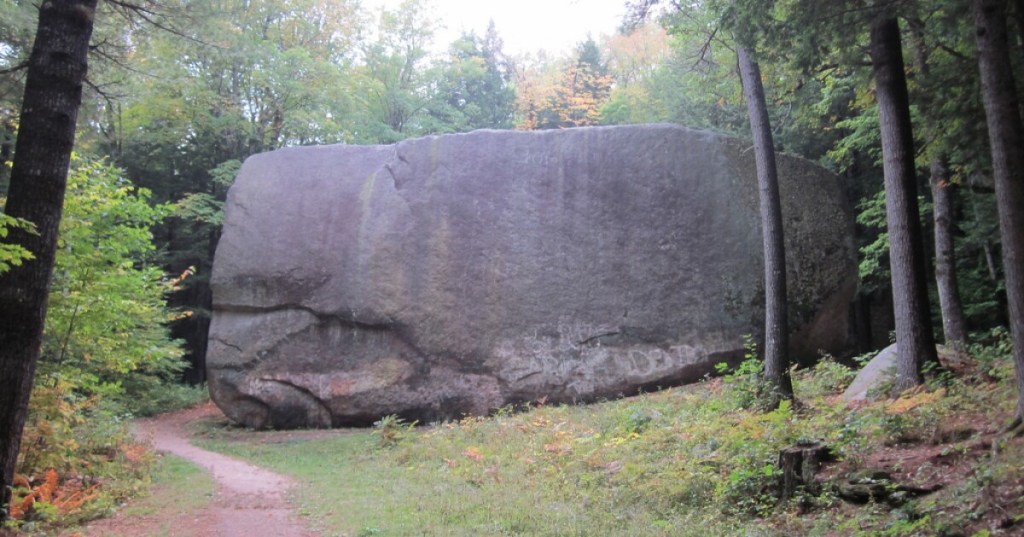

The Pleistocene glaciers, a mile thick, carried earth materials from sand grains to boulders and left them behind when they receded. Some of the boulders (known as erratics) can be seen in New England’s forests today, as can features such as eskers, or mounds resulting from soil accumulation at the edge of glaciers. Additionally, bedrock valleys were filled in, hills and ridges were flattened, and sediment was laid down in various ways.

Erratic, or boulder left behind by glaciers, in New Hampshire – courtesy of NHPR

Timberland-topped esker in Massachusetts; notice its elevation in comparison to the land surrounding it – courtesy of Mass Audubon Blogs

Satellite image of Massachusetts’ Cape Cod; it is a product of glaciers depositing sand where it is now; given its sandy composition, it is speculated Cape Cod, in part or whole, will have been claimed by the Atlantic Ocean in time, or at least see its sands redeposited in different locations – courtesy of U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit – Climate.gov

Wachusett is one of the highest mountains in New England, but it and fellow tall spots were even higher long ago; rain, wind, and glacial erosion flattened many of the region’s heights – courtesy of Visit North Central Massachusetts

Man, Who Was Here First?

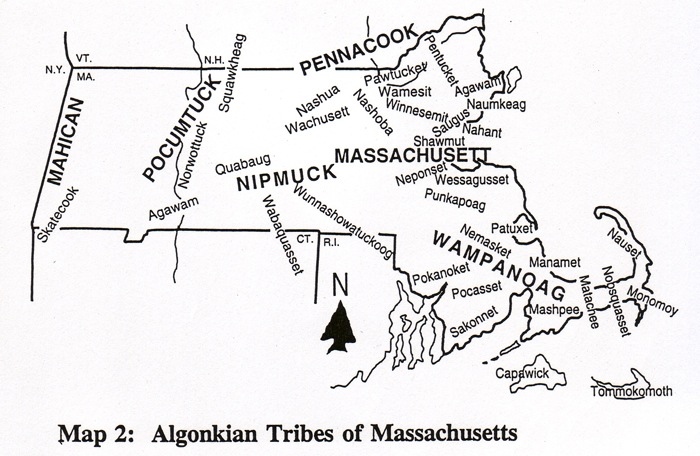

Aside: the Nashoba terrane was named after the Native American tribe of the same name, whose lands were in eastern and central Massachusetts; the Nashoba forged alliances and feuds with tribes adjacent to and near them; these included the Massachusett (namesake of Massachusetts, and translated namesake (approx. “many hills”) of Blue Hills Reservation) and the Wampanoag (famous for their role in the First Thanksgiving, though the holiday is understandably no cause for celebration for today’s Native Americans); the name of the Nashoba tribe has also been used for select Massachusetts entities- courtesy of Green Futures

Concord, MA, one of the towns Minute Man NHP is in, was originally known as Musketaquid and inhabited by various tribes. In 17th-century New England, there was vast plant diversity in the forests. These plants supported equally diverse animal types, including deer, elk, moose, and beaver. By extension, the forests supported carnivorous animals such as bears and wolves. Musketaquid’s peoples used the forests and their animals as resources in addition to their own agriculture.

The forests of New England have receded since the 17th century due to population growth, but even today one can still glean/experience their density approximation – courtesy of WBUR

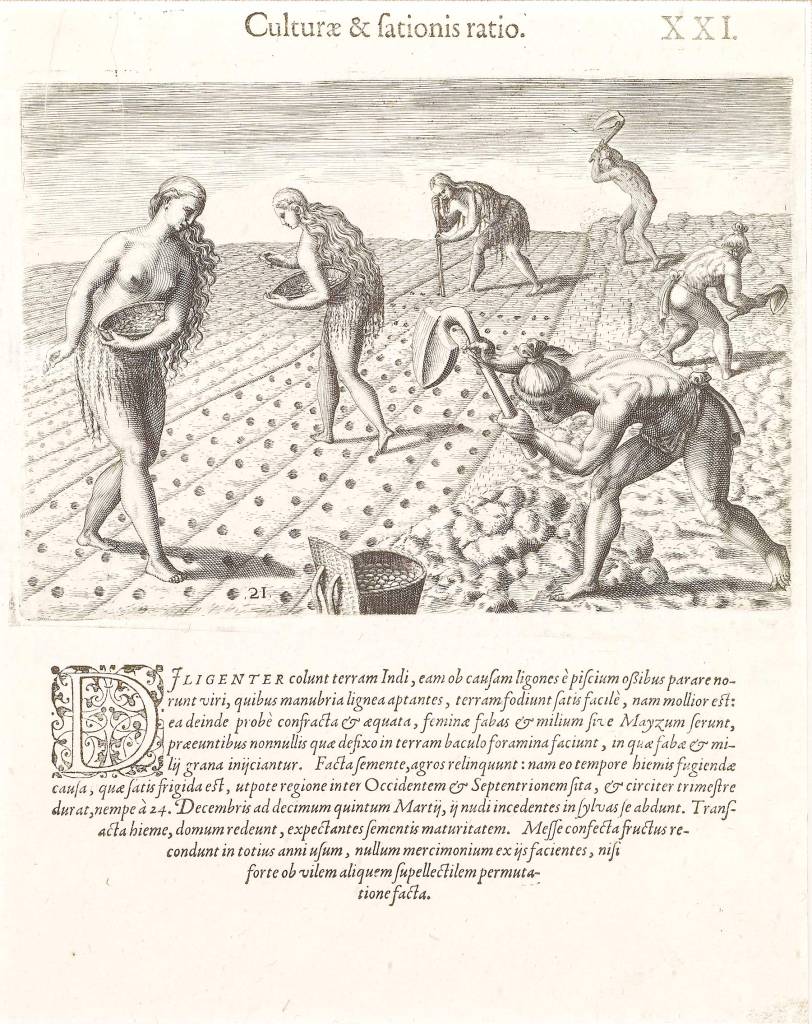

New England Native American agriculture, albeit from a colonialist perspective – courtesy of Harvard Magazine

Recreation of crop growing methods of New England’s Native Americans – courtesy of ThoughtCo

Indigenous peoples, who entered the region millennia before 17th century Europeans did, established settlements at Musketaquid for location as well as resource reasons. Musketaquid was near the convergence of two rivers and underlain by glacial soil. Denizens of Musketaquid optimized their forest resources through controlled burns to enhance agricultural practices, living areas, desirable native species and foraging game.

Musketaquid was near the convergence of the Assabet and Sudbury rivers, which collide into the Concord; the town of Concord, meanwhile, is the exact spot where the rivers converge; the Sudbury-Assabet-Concord, or SuAsCo, watershed (depicted) is part of the larger Merrimack watershed, named for the Merrimack river – courtesy of Lowell Parks & Conservation Trust

SuAsCo (green) location within the broader Merrimack watershed – courtesy of USGS

Oh Man, the Colonists are here!

Layout and residences in 17th century Concord, MA – courtesy of Concord Free Public Library

The original peoples of what became part of Concord, MA maximized resource potential while upkeeping forests. European colonists and their descendants, who drove out these indigenous inhabitants, instead centered their homes around a common meeting house while clearing forest around the settlement. Subsistence farming and animal husbandry were economic mainstays for Concord’s whites. Forests under white “caretaking” suffered due to heavy fuel demands, which resulted in intense lumber production and more cleared land plots.

Colonial-era sketch of Massachusetts’ Concord (not to be confused with other Concords, including that of New Hampshire) – courtesy of Concord Free Public Library

Each white family in Concord, Massachusetts needed an estimated 61 tons of wood per year. A 90% forested town in 1635 (year of the town’s incorporation) was 70% forested by 1700. In 1775, the town was 30% forested. By the mid 19th century, the town’s forest coverage was 10%. For what it’s worth, agriculture in this section of New England shifted westward by the late 19th century, and the rise of coal’s popularity as home warmers left new growing room for forests in the area. Timbers in Concord and the rest of New England have replenished ever since.

Concord was the first inland settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the site of the first organized armed resistance to British rule.

Courtesy of National Geographic Society

By 1775, Concord was a prosperous farming and trade hub, readily accessible via the Bay Road to Boston. There were tensions between colonial citizens and their British overlords even before April 19, 1775. The prior summer, British warships closed Boston Harbor. Royal Governor Thomas Gage implemented the unpopular Massachusetts Government Act, while dismissing the elected Massachusetts legislature the Great and General Court. In October, anti-British leaders called for a Provincial Congress in the state. Towns across what had been the Bay Colony sent representatives to this body, which assumed political power even if it was technically illegal. Colonial militia forces were seized, while arms, ammunition, and provisions were stored. The goal was to raise and equip an army of 15,000 men.

General Thomas Gage, isolated in Boston, was unsure of what to do in light of this new movement until he was given orders from his British superiors. Following their instructions, Gage sent 700 troops on a secret expedition to seize and destroy arms and supplies in rural Massachusetts. The troops’ target was Concord, 18 miles northwest of Boston, where a sizable portion of the war items were stocked. 21 companies of Grenadiers and Light Infantry were assembled. Light Infantry in particular were believed to be the ticket to success, as they were known for their speed, stamina, and intelligence. LI troops were also trained to spread out, take advantage of cover, and skirmish with the enemy. Even their clothing was thought superior: short coats and leather caps allowed them to more easily move through the woods.

Patriots clash with British forces at the Battle of Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775 – courtesy of American Battlefield Trust

Gage’s goal of destabilizing opposition was easier said than done. The forces he sent were spotted by locals, and by 4:30 A.M. word had reached Lexington that the British were marching towards Concord. Militia gathered on Lexington’s Green.

Lexington, MA’s town Green, where local militiamen gathered after hearing about the approaching British troops – courtesy of The Greater Merrimack Valley

At 5:00 A.M., the first shots were fired at Lexington, and by the next hour minute men and militias were gathered in Concord. Aside: if you’re wondering what a minute man is, it (besides naming the national historical park) refers to “a member of a group of men pledged to take up arms at a minute’s notice during and immediately before the American Revolution” (Merriam-Webster definition).

Reenactment group The Lexington Minutemen, dressed as minute men of the American Revolution – courtesy of The Lexington Minute Men

By 7:00 A.M., the British arrived at Concord, and two and a half hours later was the Battle of North Bridge.

Recreation of the Battle of North Bridge, Concord, MA – courtesy of National Guard Bureau

By 12:00 P.M., the British began to march back to Boston in the face of heavier-than-anticipated resistance. Until 3:00 P.M., the British retreated along the Battle Road, but not without inflicting what damage they could on militias, minute men, and innocent civilians alike.

British soldiers wounded and murdered many aggressors and innocents as they marched back to Boston along the Battle Road (pictured), but the minute men and militias had an advantage; the British were marching in single file with occasional hecticness, while their armed opponents weren’t restricted by the road’s boundaries; exploiting the forests on either side, minute men and militias, difficult to discern amidst the brush, fired at the British as they retreated – courtesy of National Park Service

At 3:00 P.M., British reinforcements arrived in Lexington, and several other violent incidents occurred that day until the battle, finally, ended at 7:30 P.M. Afterwards, the Siege of Boston began. From there, anti-British sentiments strengthened in New England and some of the other colonies.

There’s More to Concord than Minute Man, Man!

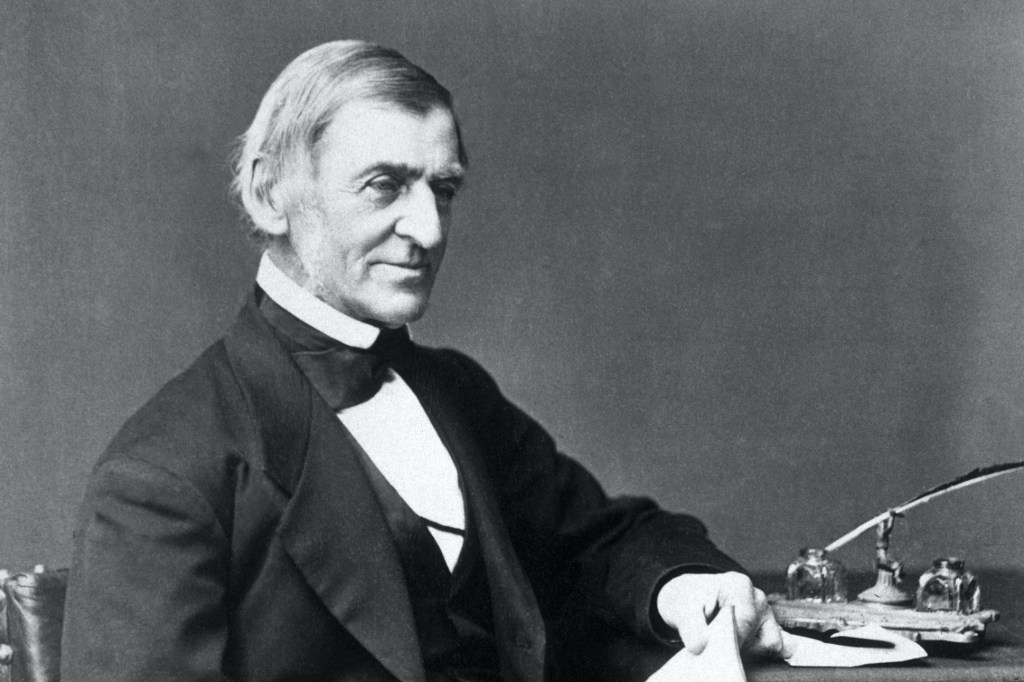

Following the Revolutionary War, Concord continued to be an important trading and commercial center for Massachusetts. In 1834, Ralph Waldo Emerson, regarded as the most influential American writer, thinker, poet, and philosopher of his day, moved to Concord. Other famous authors, such as Henry D. Thoreau and Louisa May Alcott, also lived part of their lives in Concord.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, an influential American intellectual of the 19th century – courtesy of Poetry Foundation

In the 1850s, Concord was a stop on the Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes from the south to the north, Canada, and Mexico where slaves tried to reach freedom.

Routes of the Underground Railroad – courtesy of PBS

A site in Concord which was part of the Underground Railroad – courtesy of Only In Your State

Throughout the rest of the 19th century, Concord locally developed a reputation as a small scale crop center. Outlying farms prospered; dairying and market-gardening, including asparagus and strawberry growth, were outcomes. Immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Scandinavia, and Canada helped along this agriculture boom in the town. West Concord, meanwhile, became a contributor to local industrial sectors.

Homestead which contributed to Concord, MA’s 19th century agriculture – courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations

Concord’s agriculture was famous enough locally so as to be marketed nationwide; the most famous fruit from the town is the Concord Grape, which has been used for innumerable products such as the one pictured – courtesy of Smucker’s

Some are born in the town and live there most of/the entirety of their lives, some move there for its historic significance, some move there for its educational and cultural offerings, some move there since it’s close to Boston, and some move there simply because of nature.

Walden Pond, Concord, Massachusetts – courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine

What About the Plants and Animals, Man?

Minute Man NHP has approximately 250 documented species of plants, such as sugar maple, white oak, European buckthorn, and Morrow bush honeysuckle.

Sugar maple … only thing that’s missing is the syrup – courtesy of Oakland Nurseries

White oak – courtesy of Nebraska Forest Service

European buckthorn; this is invasive in the Americas, almost as invasive as the Europeans and their descendants – courtesy of Meewasin Valley Authority

Morrow bush honeysuckle, another invasive species in the Americas – courtesy of Missouri Department of Conservation

On top of 160 bird species and 20 reptile and amphibian species, Minute Man NHP is home to eastern cottontail, deer mouse, red fox, white-tailed deer, and fisher (known as “fisher cats” commonly, but their name is regardless inaccurate as they rarely if ever seek fish in their diet).

Eastern cottontail, but it isn’t named Peter and there’s no bunny trail in sight – courtesy of New Hampshire PBS

Deer mouse … no antlers (which would be too heavy for it anyway) – courtesy of USU Extension – Utah State University

Red fox … though some would say its coloration is orange instead – courtesy of Natural Resources Council of Maine

White-tailed deer, working on its leg grindset – courtesy of Ohio Department of Natural Resources

Fisher, or as some call it “fisher cat”, in Massachusetts; curiously, our neighborhood has a fisher which traverses it and adjacent ones (and maybe further afield at times) for food – courtesy of Bat Guys

Man, Do You Want to Go to Minute Man National Historical Park Now?

We hope you do.

Physical satellite map of Minute Man National Historical Park; North Bridge goes over the Concord river, and the combo of the Assabet (left) and Sudbury (right) is visible; the pond along the Sudbury (southwest of Walden Pond) is Fairhaven Bay, which we commonly hike at – courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory

Courtesy of National Park Service

Sources:

- “Geology of Minute Man NHP”. National Park Service. 2 November 2020 (Updated). https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/geology-of-minute-man-nhp.htm#:~:text=The%20major%20features%20of%20the,glaciers%20were%20like%20massive%20bulldozers.

- “Forests at Minute Man NHP”. National Park Service. 31 October 2020 (Updated). https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/forests-at-minute-man-nhp.htm

- “History of Concord”. Concord Museum. https://concordmuseum.org/gateway-to-concord/history-of-concord/

- “April 19, 1775”. National Park Service. 29 September 2022 (Updated). https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/april-19-1775.htm

- “Minuteman”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/minuteman

- “Plants”. National Park Service. 30 October 2021. https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/nature/plants.htm

- “Animals”. National Park Service. 8 December 2021.

ancient publeon Casa Riconda Chacoan Great Houses Chaco Culture National Historical Park cliff palace Hugo Pavi isla mujeres Junior Park Ranger program Kivas long house mesa verde Mesa Verde audio tour mug house National Park North Beach petroglyphs Petroglyph trail Pueblo Bonito Pueblo del Arroyo Recreation.gov reviews Square House Tower Supernova tour ultramar Una Vida Wetherill mesa whale shark snorkel