- Give A Dam About Geology? Let This Be An Introduction, As We Have Trouble With All The Terms Here!

- Not Giving A Dam

- Giving A Dam

- Dam Flora, Dam Fauna

- Dam, Is It Time To Head To Hoover?

The Hoover Dam is along the Colorado and on the borders of Nevada and Arizona.

Even when we were there, we noticed – dry as the region is – there’s a bit more water normally – courtesy of CNN

Courtesy of The American Southwest

Give A Dam About Geology? Let This Be An Introduction, As We Have Trouble With All The Terms Here!

The natural rocks surrounding the Hoover are Precambrian metamorphic rock, Tertiary volcanic and plutonic rock, and Quaternary gravels. Paleozoic rocks are in the roof pendants in Tertiary plutons and xenolithic blocks in mafic lava flows. Barring isolated pieces, the Hoover’s rocks are broken along late Miocene faults with complex slip components and Mead Slope left-lateral strike-slip fault. Adjacent Lake Mead has Precambrian gneiss, amphibolite, schist, and pegmatite. Dam, that’s a ton of terminology.

Precambrian metamorphic rock – courtesy of National Park Service

Tertiary volcanic rock – courtesy of Imaggeo – European Geosciences Union

Tertiary plutonic rock – courtesy of Australian Museum

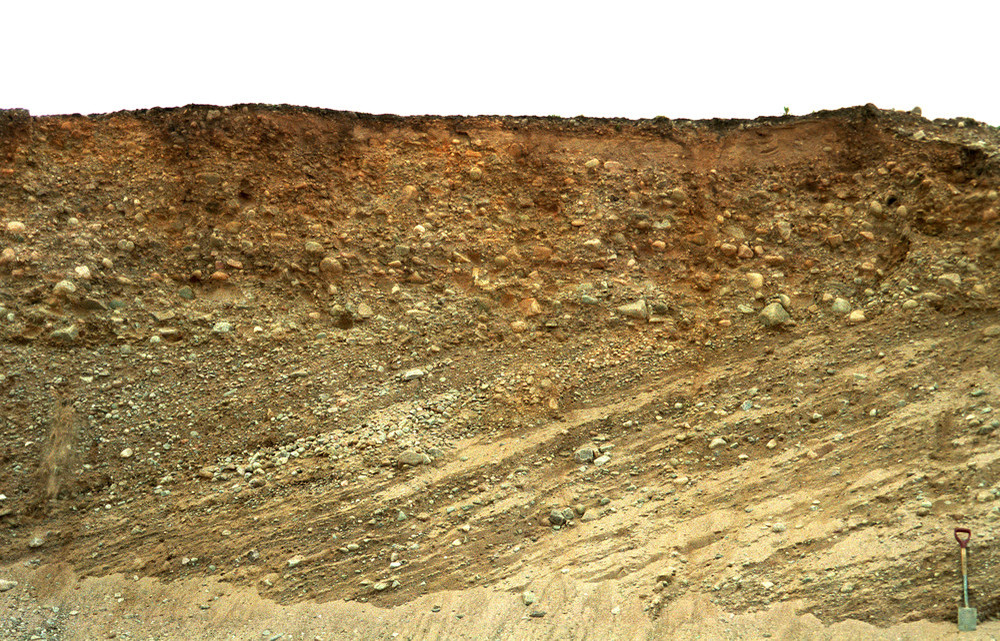

Quaternary gravels – courtesy of BGS Earthwise – British Geological Survey

Paleozoic rock – courtesy of MIT News – Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Miocene rock – courtesy of California State University, Long Beach

Lake Mead, also on the border of Nevada and Arizona – courtesy of NBC News

Geology around and beneath Lake Mead – courtesy of National Park Service

Precambrian gneiss – courtesy of National Park Service

Precambrian amphibolite – courtesy of Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey

Precambrian schist – courtesy of Answers Research Journal

Not Giving A Dam

There was no Native American settlement right at where the Hoover Dam itself is, but there were a few nearby. Over 1,000 years ago, Native Americans settled where Lake Mead is today. The inhabitants of the area had a culture which paralleled that of the nearby Ancestral Puebloans. The Hopi of Arizona claim descent from some of these peoples (which they refer to as “Hisatsinom”).

One of us took a college course on Native American history; we went in knowing European colonization was devastating (anywhere it went, not just here), but we learned it had another dimension we weren’t aware of; notice on the map that the Hohokam and Mogollon’s spheres weren’t originally divided by a U.S.-Mexico border; the artificial boundaries meant tribes were forced into worlds apart, even if their members lived right next to each other; a similar situation occurred when Europeans colonized Africa – courtesy of In the Eyes of the Pot

The American Southeast, as the Southwest, is a microcosm of the genocides Europeans and their descendants inflicted on Native Americans; pictured are the original tribal territories of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee (whose North Carolinian reservation we visited), Creek, and Seminole, the “Five Civilized Tribes” – named for their adoption of white American cultural customs; this partial assimilation was a conscious choice on the part of the tribes in the hopes of warding off westward white expansion; this was in vain in the long run, as soon southern whites’ demand for land meant the U.S. government evicted the FCTs; they were forced to march towards newly-U.S.-conquered lands in what is today Oklahoma in what became known as the Trail of Tears (named for the disease, death, and other misfortunes which befell the Native Americans forced to participate) – courtesy of Vox

For comparison, here is a map of the tribes/ethnicities in Africa against the modern political boundaries; the European “Scramble for Africa” was a disaster in more dimensions than the obvious, best-known effects; as in the case of Native Americans, African tribes which were united/semi-united and had local allies were separated by artificial borders; in some cases, tribes which had been enemies (some for generations) were forced to live side by side; it’s no wonder, then, that some conflicts in modern Africa occur along tribal lines – courtesy of Vox

Pueblo Grande de Nevada (a.k.a. The Lost City), a complex of villages near what became the Hoover Dam, lent key insight into the peoples who resided there. The Ancestral Puebloans, it was learned, were one of a succession of peoples who lived in the area over time. The earliest known peoples to live in the area were the Basketmakers, who lived side by side with the Puebloans even after the latter settled in the region. The last known people to have lived at PGN itself were the Paiute.

The Lost City Museum, Overton, Nevada (near where Pueblo Grande de Nevada was) – courtesy of Daytrippen

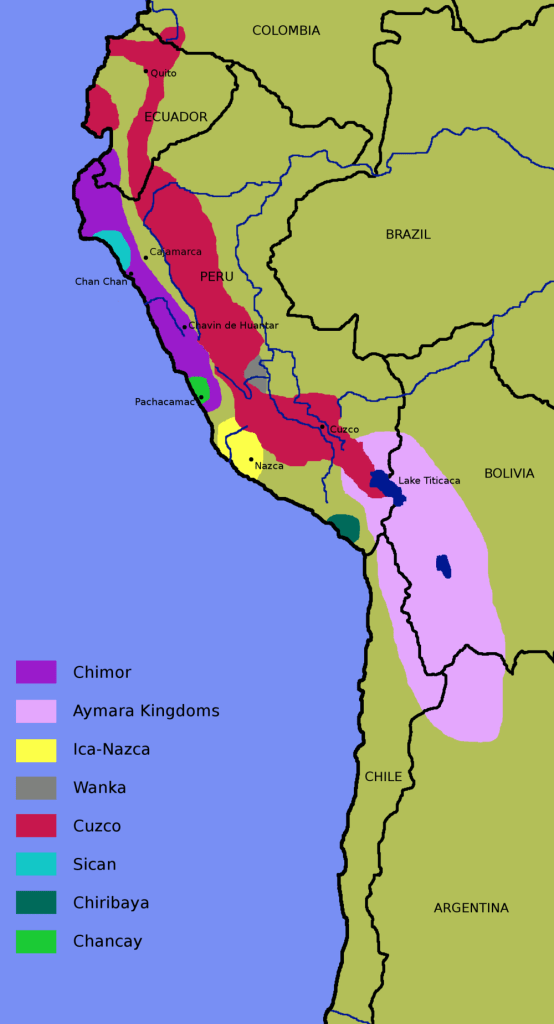

Pueblo Grande de Nevada is far from the lone exemplification of indigenous cultural succession in the Americas; the map above is a collection of civilizations/societies which existed in the Andes, and whose territories were absorbed (by the rulers of Cuzco) into the Inca Empire; the Quechua peoples (descendants of many of the empire’s inhabitants) are at times referred to as Inca/Incan by scholars and travel businesses, but it’s incorrect on a technical and cultural level; Spanish colonizers saw that the rulers of the Inca Empire referred to themselves as Inca, and assumed the peoples they lorded over were called the same; in actuality, Inca was only ever a moniker for the imperial royalty; aside, notice the southernmost area on the map is the Aymara Kingdoms; pre-Spanish colonization, the Quechua (under pre-, proto-, and actual Inca leadership) were in conflict with the primarily loosely connected series of monarchies in what are now southeast Peru, southwest Bolivia, northeast Chile, and northwest Argentina; eventually, the Aymara Kingdoms were conquered by Inca forces and assimilated politically; culturally, the peoples of the region exist to the present day – courtesy of Museum of Native American History

Basketmakers constructed their homes as underground pit houses, while the Puebloans built above ground structures. PGN’s houses sometimes had 20 rooms or more (one contained 100 rooms).

Structure of houses at Pueblo Grande de Nevada – courtesy of Legends of America

As the Hoover Dam was constructed, and Lake Mead was formed, it was realized the Lost City was to be submerged. The National Park Service, in conjunction with the State of Nevada, gathered items from the site. Many sites connected to the Lost City remained above water and were transported to the Lost City Museum of Archaeology in Overton, Nevada. As for Pueblo Grande de Nevada itself, the structures are in the depths of Lake Mead.

Giving A Dam

In 1905, a series of farmer-made canals was ruined when the Colorado broke through their barriers. In response, the U.S. Bureau of Land Reclamation planned for a massive dam at the Colorado’s point on the Arizona-Nevada border. It was meant to gather farming water and hydroelectric power for a developing American Southwest. Bureau director Arthur Powell Davis, in 1922, proposed a multipurpose dam in Black Canyon. The project was met with skepticism, as it was estimated to cost $165 million USD and representatives from six states were concerned the water would primarily go to California instead of multiple places. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover formed the 1922 Colorado River Compact to divide the water equally among states in the region. President Calvin Coolidge authorized the Boulder Canyon Project in 1928. In 1930, Secretary of the Interior Ray L. Wilbur declared the structure, in honor of the new president’s contributions, would be named the Hoover Dam. The name wasn’t officialized until 1947.

Construction of the Hoover Dam – courtesy of LetsBuild

Hoover Dam Diagram – courtesy of National Park Service

The dam’s construction was contracted in March 1931 to Six Companies, a group of construction firms which pooled its resources to conjure the $5 million performance bond. Construction of the dam was an arduous process, and many laborers died in the making. The final concrete block was laid, 726 feet above the canyon floor, in 1935. On September 30, 20,000 witnessed president Theodore Roosevelt commemorate the dam’s completion. The Hoover Dam’s completion led to the population rise in cities such as Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles, and impacts the region to this day. The 17 turbines are capable of irrigating 2 million acres, and generate enough hydroelectricity to fuel 1.3 million homes. The dam was designated a National Historical Landmark in 1985 and one of America’s Seven Modern Civil Engineering Wonders in 1994. It receives 7 million visitors annually, while Lake Mead, the world’s largest reservoir, receives 10 million visitors annually.

Dam Flora, Dam Fauna

Barrel cactus, cholla cactus, desert marigold, prickly pear cactus, and more are near the dam.

Barrel cactus – courtesy of The Columbus Dispatch

Cholla cactus – courtesy of Desert USA

Desert marigold – courtesy of Las Pilitas Nursery

Prickly pear cactus – courtesy of Medical News Today

Hoover Dam wildlife encompasses bighorn sheep, ringtail cats, greater roadrunners, canyon wrens, turkey vultures, desert tarantulas, mojave rattlesnakes, and more.

Bighorn sheep … indeed – courtesy of National Park Service

Ringtail cat … don’t expect it to be near a litter box – courtesy of San Antonio Express-News

Greater roadrunner … no Wile E. Coyote in sight here! – courtesy of National Park Service

Canyon wren – courtesy of Eastside Audubon

Turkey vulture … not a recommended dish to pair with stuffing, cranberry sauce, and mashed potatoes – courtesy of Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

Desert tarantula – aside, we’ve seen the commonly-envisioned black and orange tarantula in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula; our guide got him out of his burrow by mimicking what their prey do unawares; he was a tiny tarantula, but our guide explained female tarantulas can be even bigger and lurk in the Yucatan’s trees – courtesy of National Park Service

Mojave rattlesnakes … sweet dreams – courtesy of Victorville Daily Press

Dam, Is It Time To Head To Hoover?

We say yes, dam it!

Courtesy of Las Vegas Review-Journal

Sources:

- Mills, James G. “GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF THE HOOVER DAM 7.5 QUADRANGLE”. ResearchGate (Sourced from DePauw University). January 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255608366_GEOLOGIC_HISTORY_OF_THE_HOOVER_DAM_75’_QUADRANGLE#:~:text=The%20Hoover%20Dam%20area%20contains,blocks%20in%20mafic%20lava%20flows.

- “The Lost City”. National Park Service. 19 October 2020. https://www.nps.gov/lake/learn/the-lost-city.htm

- “Hoover Dam”. History. 14 April 2010 (Original Publication), 29 September 2020 (Updated). https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/hoover-dam

- “Plants at Hoover Dam/Lake Mead”. Digital Desert. https://digital-desert.com/hoover-dam/e-04.html

- “Wildlife at Hoover Dam”. Digital Desert. https://digital-desert.com/hoover-dam/e-03.html