Chaco Canyon National Historic Park lies near the San Juan Basin of New Mexico which is near the southeastern edge of the Colorado Plateau. It is – as with so many other sites in the American Southwest – a geographical, natural, and historical wonder.

Table of Contents:

- Table of Contents:

- Geological Past

- First People

- The Kiva

- The Great Kiva at Casa Rinconada

- Wash, Arroyos, Flora and Agriculture

- Astronomy

- National Park

- Learn More!

- Future

Geological Past

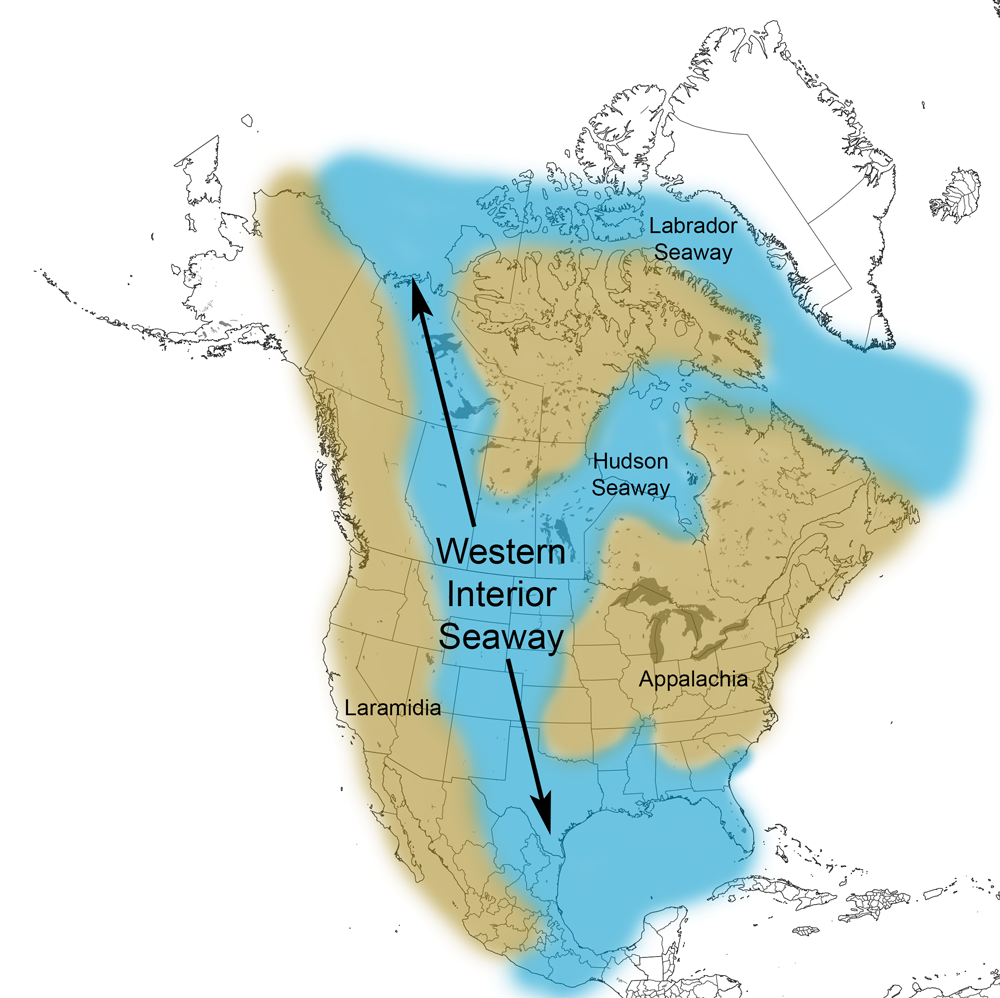

Chaco Canyon’s rock formations are 85 to 75 million years old (in other words, they stem from the Late Cretacious period). In that time, the middle of North America, from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico, was submerged by a saltwater body known as the Western Interior Seaway, or WIS. The coasts of the WIS in the American Southwest were subtropical, defined by a swampy landscape and flora resembling today’s eucalyptus and magnolia (among many other plants). Throughout its lifetime, the WIS expanded and receded, creating layers of sediment on its floor all the while. These layers transformed into what is today called the Mesa Verde group. From oldest to youngest, the layers of this group are: Crevasse Canyon Formation, Point Lookout Sandstone, Menefee Formation, Cliff House Sandstone, Lewis Shale, and Pictured Cliffs Sandstone. Of these, Menefee and Cliff House are visible within the main canyon body; Lewis Shale and Pictured Cliffs are viewable only on the park’s northern boundary; Crevasse Canyon is viewable only in the park’s Kin Ya’a unit; and the Point Lookout Sandstone isn’t visible within the park.

The Western Interior Seaway is one reason marine and maritime fossils are in unlikely places, including the anything-but-oceanic American Southwest – courtesy of Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life

Difficult as it may be to imagine in the 21st century, large chunks of North America – even the famously dry Southwest – were subtropical and boggy – courtesy of The New York Times

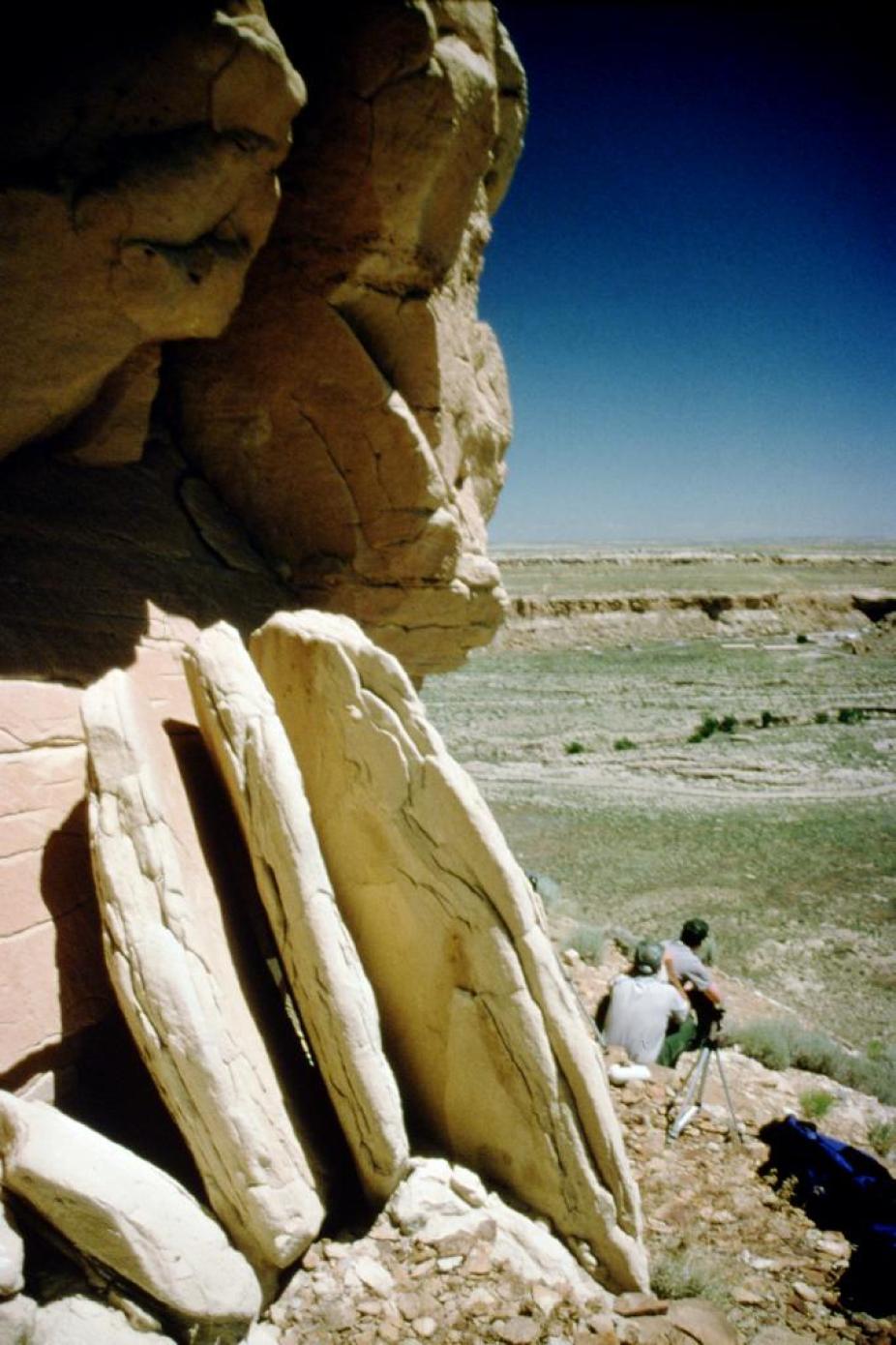

Menefee formation (pictured), along with Cliff House sandstone, is visible within the primary canyon section – courtesy of USGS

First People

Many Native American tribes claim descent from the Chacoan civilization. These include the Navajo, in addition to modern Puebloans such as the Hopi and Zuni (who claim descent from Ancestral Puebloans generally). It remains hotly contested, and probably will be for the foreseeable future, but what can’t be contested is Chaco thrived from 800 A.D. to 1250 A.D.

Several Great Houses, the most famous of them Pueblo Bonito, served as residences for Chaco’s elites and locations for religious ceremonies. In fact, it’s speculated the elites’ control of those ceremonies was what gave them socioeconomic esteem in their society in the first place. Unlike in Europe and the majority of the rest of the world, Chacoans, or at least their elites, were matrilineal, or had special status and its privileges passed through the mother’s side. The rest of the populace lived in smaller residences near the Great Houses.

It’s unknown if the elites were a dynasty, as some researchers have suggested, or merely happened to be matrilineal for over 300 years. It’s unknown if the Chacoan elites’ direct control went beyond Pueblo Bonito, or even the canyon itself. No matter which case applies, Chaco’s influence was amazingly widespread. Dozens of settlements which took after its architecture and organization have been found in Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona.

This far-reaching influence makes sense when one considers the Chaco civilization, and others like it/taking after it were connected by a sophisticated-for-their-time network of roads.

T-shaped doors in Chaco Canyon – Own Work

Reconstruction of Pueblo Bonito – courtesy of Archeyes.com

Ancient Chacoan Roads and Sites (red lines and red dots respectively), in coordination with modern National Parks lands (green patches) – courtesy of Science.org

The Kiva

Kiva is derived from a Hopi term for specialized round and rectangular rooms in modern Pueblos, though archaeological findings hint ancient kivas served the same function as modern ones. Chacoan kivas specifically were round, semi-subterranean, and built in Great Houses. Daily domestic life and religious ceremonies defined kivas then as they do now.

Intriguingly, there were two varieties of kiva in Chaco. The first was the Great Kiva, which was where social, political, and ceremonial activities occurred. The second was the Small Kiva, which was used to house small, kin-based family units.

Kiva structures (as with other American Southwest architecture) took advantage of environmental factors to make life more comfortable for those who lived there; a common occurrence was dwellings were cool in summer and warm in winter – courtesy of Crown Canyon Archeology Center

The Great Kiva at Casa Rinconada

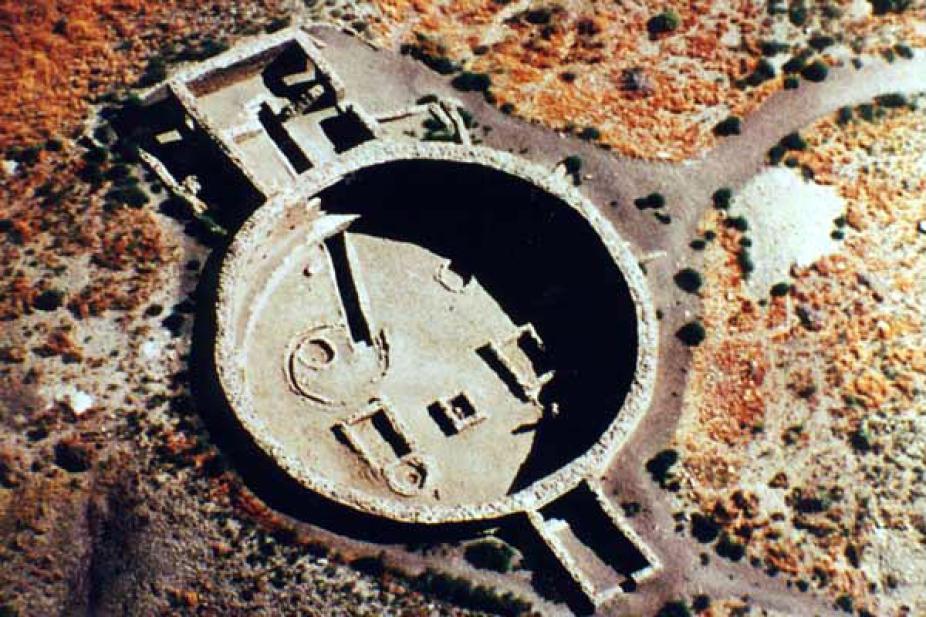

Even among Chaco’s Great Kivas, the one at Casa Rinconada is a standout. Located six miles from the visitor center on the nine-mile Canyon Loop Drive, the Casa Rinconada isn’t embedded in a large building complex but is a distinct hilltop building separate from the other Great Kivas. It’s partly above ground while the majority of kivas have their roofs at ground level, and at four to five meters deep is one of the largest known Great Kivas.

Geometrically, Casa Rinconada is the most advanced of Chaco Canyon’s settlements. Its symmetry axis has two t-shaped doors aligned north-south to within twenty degrees. The interior wall’s small niches are equally spaced and positioned so lines defined by opposing pairs of niches all have their center within 10 centimeters of the kiva’s center. Circular masonry foundation sockets for the four roof posts on the kiva floor form a square, itself also centered on the kiva center within 10 centimeters. Its sides are oriented to within thirty degrees of either the north-south or east-west directions.

What’s more, it’s believed by some researchers Casa Rinconada was meant to represent the Ancestral Puebloan cosmos. If this is a correct interpretation, it can be combined with its unique design to explain why this was used for religious ceremonies. In light of all this, it could’ve been important to elites and Chacoan society even by the standards of their Great Kivas.

Aerial view of Casa Rinconada – courtesy of NCAR High Altitude Observatory

Views of Casa Rinconada; note the design’s symmetry – Own Work

Wash, Arroyos, Flora and Agriculture

“Wash” and “arroyo” are sometimes used as if they signify separate natural entities. In reality, they’re essentially one and the same. A wash is a shallow channel which follows a land’s contours and allows water to flow, or wash, from higher to lower elevations. Arroyo is a Spanish term for a creek or small river which may or may not have water at certain points in the year. Chaco Wash is both a wash and an arroyo. It descends from a higher elevation into the lower elevation of the canyon floor, is a narrow flow of water, and depending on the time of year is nothing but a dry bed which blends into the desert.

Chaco Wash’s banks are lined with shrubs and bushes, even if there is no water flowing. The original residents received some of their water supply through this wash. The wash/arroyo, being what it was, wasn’t enough to sustain agriculture for a place as highly populated-for-the-region as Chaco. Nor was direct rain, by itself or combined with the wash/arroyo, enough. To compensate, and ensure peoples’ survival, Chacoans utilized a sophisticated system of canals, or water diversion channels meant to direct rainfall to farm fields. Outside aid (food and water supplements from other settlements) was present, but instead of a commonality (as some researchers have thought) it was only used during emergencies (such as droughts which affected one, a few, or even all of the communities in the same road network). In any event, common crops for Chaco included maize, beans, and squash, which so happened to be important to several other Native Americans in the Southwest and beyond.

Chaco Wash winds through the canyon during a rare snowy period for the area; in the background on the right is Fajada Butte – courtesy of USGS

Painted reconstruction of an Ancestral Puebloan farming – courtesy of World history

Chaco, despite being part of a desert ecosystem, is a refuge for flora and fauna which have struggled in other parts of the same area thanks to grazing, mining, and more. Pinyon-juniper woodlands, cottonwood, willow, and more comprise the flora, while the fauna which directly or indirectly benefit from these include elk, badgers, bats, and lizards.

Pinyon-Juniper (or Juniper-Pinyon) forest, common in this part of the American Southwest – courtesy of Basin and Range Watch

Various bat species are a fraction of the animals which reside around Chaco – courtesy of DesertUSA

Astronomy

Archaeological evidence suggests Chacoans (as with the Mayans further south) were skilled astronomers. Chaco’s night sky is exceptionally dark due to its isolation from any civilized area, which makes astronomical observations relatively easy. In an age without electricity, Chacoans had an advantageously clear sky. It’s no wonder their knowledge of the then-observable cosmos was extensive for their era, as evidenced by the Sun Dagger and a depiction of the July 4, 1054 A.D. supernova.

Fajada Butte is perhaps the last thing someone in today’s time would associate with astronomy … that is, unless one is aware of what the Chacoans used it for – courtesy of PeakVisor

The Sun Dagger is located on Fajada Butte, which visitors can spot at the entrance to the canyon proper (the hill is off-limits to tourists today thanks to previous ones causing erosion that affected the astronomical component). It consists of a set of spiral petroglyphs etched into a cliff face behind three giant slabs of rock. These slabs serve as a solar marker. The rocks, combined with solar rays going through it, affect where the sun shines on the spirals at certain times. At summer solstice, a vertical light shaft hits the big spiral’s center. At winter solstice, two light shafts bracket the big spiral. At spring and fall equinoxes, light shafts hit the center of the small spiral. Atop this, findings imply the spirals may track the 18.6-year lunar cycle.

Sun Dagger petroglyphs – courtesy of The Shallow Sky

3 slab slit – courtesy of High Altitude Observatory

Demonstration of slabs’ effects on solar rays’ spiral impacts – courtesy of Solstice Project

One pictograph in Chaco is located on a cliff face five hundred meters northeast of Pennasco Blanco ruin. Firm evidence points towards this painting being a depiction of a supernova which occurred July 4, 1054 (the same supernova was also documented in China, Japan, and (to a far lesser extent) Europe). The supernova, in the grand cosmic scheme, left behind the famous Crab Nebula in the constellation Taurus. In terms of human history, it demonstrates Native Americans were more advanced peoples than Europeans ever gave them credit for.

Pictograph depicting the July 4, 1054 A.D. supernova, as seen by Chacoans – courtesy of EarthSky

The 1054 A.D. supernova pictograph contains a moon, a star shape to the left representing the supernova itself, and a life-size handprint meant to indicate the site is sacred. Additional information extracted from the same site hints at dawn, on July 5, 1054 in the American Southwest, the moon was within three degrees of the supernova, its crescent oriented as on the pictograph (provided it is viewed looking up with one’s back to the cliff, as the pictograph’s makers likely did). Given the width of the moon appears half a degree (as the moon at the time was in a waning phase), the painting is the closest Chaco’s inhabitants could get to a true scale rendition of the supernova.

Evening sky above Chaco Canyon; this photograph makes one wonder what the sky looked like during the height of Chacoan civilization, when city lights didn’t pierce the cosmos – courtesy of Deseret News

National Park

Chaco Canyon National Monument was established in 1907. Aztec Ruins National Monument was established in 1923 and expanded several times. Five Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Sites were established in 1980. In 1987, all of these were merged to create Chaco Canyon National Historic Park.

Aztec Ruins National Monument is near Chaco Canyon itself; Aztec existed as an unaffiliated site from 1923 until its absorption into Chaco Canyon National Historic Park in 1987 – courtesy of TravelAwaits

Learn More!

by R. Gwinn Vivian (Author), Bruce Hilpert (Author)

https://www.amazon.com/Chaco-Handbook-Encyclopedia-Guide-Canyon/dp/1607811952

https://www.amazon.com/Chaco-Astronomy-Ancient-American-Cosmology/dp/0943734460/ref=pd_lpo_3?pd_rd_w=qe2Is&content-id=amzn1.sym.116f529c-aa4d-4763-b2b6-4d614ec7dc00&pf_rd_p=116f529c-aa4d-4763-b2b6-4d614ec7dc00&pf_rd_r=J4N6YDAYZ2SRBX9MPQ8J&pd_rd_wg=BHKwc&pd_rd_r=43ebc4a5-d7b7-4291-9bcc-4ed4184b56f5&pd_rd_i=0943734460&psc=1

David E. Stuart

https://www.hamiltonbook.com/the-ancient-southwest-chaco-canyon-bandelier-and-mesa-verde-paperbound

Future

Chaco Canyon will, for generations to come, be a geologic marvel, a natural wonder, and a testament to how “modern” fields such as astronomy are far older than some people believe. Additionally, University of Cincinnati professor Vernon Scarborough explains, “Our work and that of other colleagues is beginning to show the significance of low-tech adaptations in attempting to accommodate life on Earth … A greater understanding of just how these ancient, ‘primitive’ systems adapted and function merits a thoughtful reassessment given the social and environmental stress we face globally today”.

Sources:

- “Geology”. National Park Service. 24 February 2015 (Updated). https://www.nps.gov/chcu/learn/nature/geology.htm

- Balter, Michael. “Ancient DNA Yields Unprecedented Insights into Mysterious Chaco Civilization”. Scientific American. 22 February 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ancient-dna-yields-unprecedented-insights-into-mysterious-chaco-civilization/

- “‘Kivas’ of Chaco”. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/chcu/slideshow/kivas/kivasintro.html#:~:text=Kivas%20are%20an%20important%20Southwestern,ancient%20kivas%20served%20similar%20functions.

- “Casa Rinconada”. National Park Service. 18 December 2017. https://www.nps.gov/chcu/planyourvisit/casa-rinconada.htm

- “Casa Rinconada”. High Altitude Observatory. https://www2.hao.ucar.edu/education/prehistoric-southwest/casa-rinconada

- Thompson, Clay. “What is the difference between arroyo, gulch and wash?”. AZ Central. Published and Updated 20 July 2015. https://www.azcentral.com/story/travel/local/history/2015/07/20/difference-arroyo-gulch-wash-terminology/30410531/

- “Ancestral people of Chaco Canyon likely grew their own food”. Science Daily. 3 July 2018. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/07/180703154919.htm#:~:text=Experts%20have%20determined%20that%20the,Canyon%20largely%20were%20self%2Dsufficient.

- “Nature & Science”. National Park Service. 11 September 2022 (Updated). https://www.nps.gov/chcu/learn/nature/index.htm#:~:text=A%20number%20of%20ecosystems%20comprise,numerous%20scrub%20and%20wildflower%20communities.

- “Supernova Pictograph”. High Altitude Observatory. https://www2.hao.ucar.edu/education/prehistoric-southwest/supernova-pictograph#:~:text=A%20pictograph%2C%20associated%20with%20the,located%20in%20the%20constellation%20Taurus.

- “Ancient Observatories: Chaco Canyon”. Exploratorium. https://www.exploratorium.edu/chaco/HTML/fajada.html

ancient publeon Casa Riconda Chacoan Great Houses Chaco Culture National Historical Park cliff palace Hugo Pavi isla mujeres Junior Park Ranger program Kivas long house mesa verde Mesa Verde audio tour mug house National Park North Beach petroglyphs Petroglyph trail Pueblo Bonito Pueblo del Arroyo Recreation.gov reviews Square House Tower Supernova tour ultramar Una Vida Wetherill mesa whale shark snorkel