- Baxon to the Saxons

- Steern vs. Stern

- Hanseatic League

- Mittelniederdeutsch

- Lost Status of Low German

- Westphalian

- Mennonite Low German

- The Blog Authors in Relation to Low German

Plattdeutsch, aka Low Saxon or Low German, is a northern German dialect continuum distantly related to those of central and southern German lands.

#1-10 are Plattdeutsch/Low Saxon/Low German; the rest are Low Franconian, which PD/LS/LG are closer to than Standard German; LF, in turn, are closer to English and Frisian (the latter around Leeuwarden, left of #1, and a dot between #4 and #3) than German continuums – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Baxon to the Saxons

Low German’s moniker, in Germany and its translation to English, hints at the geography of northern Germany, where it was widely spoken (and still is in shrinking pockets). Northern Germany is flat minus high hills and low mountains, hence the “Low” or “Platt” descriptive.

Plattdeutsch’s ancestor is Old Saxon, spoken by the Saxon tribal alliance, whose later genetic and cultural mingling with the Angles formed the Anglo-Saxons, who militarily and culturally invaded Britain. Old English and Old Saxon read similarly for a reason.

Courtesy of Building Blocks of Low Saxon: An Introductory Grammar

The Saxons are so recognized globally that the Angles are seen as an afterthought, despite contributing to the culture which superseded Celtic England; the Jutes were later assimilated by the Danes – courtesy of MythBank

Not all Saxons chose to invade Britain. Those within mainland Europe kept their language, which phased to Plattdeutsch as it’s known today.

Steern vs. Stern

Laway is a German band whose output is mostly East Friesland Plattdeutsch. One of their songs is “Dusende van lüttje Steerns (Holocaustkinner)”, a tribute to the youth murdered during the series of events. The word Steern is a Low German equal to Standard German’s “Stern” or star.

It’s a difference broadly applying to northern vs. southern German lands. It’s a making of the High German Consonant Shift, where the further south, and higher elevation, German speakers were, the more their speech changed (partly explaining harshness of German in pop culture).

According to Langster, “High German and Low German originally [contained] similar consonants – [t], [p], and [k]”, and didn’t after the shift. The common switches were as follows:

- [p] became [pf] or [f], which is why there are two different words for “apple”: [appel] in Low German and [apfel] in High German.

- [t] became [s] or [ts] – we can hear that today in the different pronunciation of the words [dat] and [wat] in Low German, as opposed to [das] and [was] in High German.

- [k] changed to the fricative [ch] – Low German [maken] became [machen] in the High German dialect.

Langster adds, “Grammar and vocabulary … also differ in High and Low German … For example, Low German … present progressive form of verbs … resulted from its connection to the Old Dutch language. In the northern dialects of Low German, the past participle is … created without the prefix ge- (geschlafen vs. slapen for “slept”) … Low German words … often differ significantly from High German words. For instance, Moin for “Hello,” Bidd for “Please,” or Wat is dien Naam? for “What is your name?””. Concerning “Moin”, “Bidd”, and “Wat is dien Naam?”, their respective Hochdeutsch equivalents are, according to Google Translate, “Hallo”, “Bitte”, and “Wie heißt du?” (ß being “ss”, two s’s; this symbol isn’t found in Swiss German writing).

Hanseatic League

Plattdeutsch is seldom spoken day-to-day modernly, but it wasn’t always the case. It was the Hanseatic League’s lingua franca.

There’s no discernable “start point” time-wise and location-wise for the league, though an early boost was Lübeck, founded 1158 but ascended to economic boom during the 1200s. Its center was a mercantile enclave with a market area, specialized shops and craft areas, a town hall, merchant houses, warehouses, and a merchant’s church built specifically for business and worship. Its town constitution was replicated by other northern German towns and cities due to the financial prospects.

Lübeck, Schleswig-Holstein – courtesy of Orana Travel

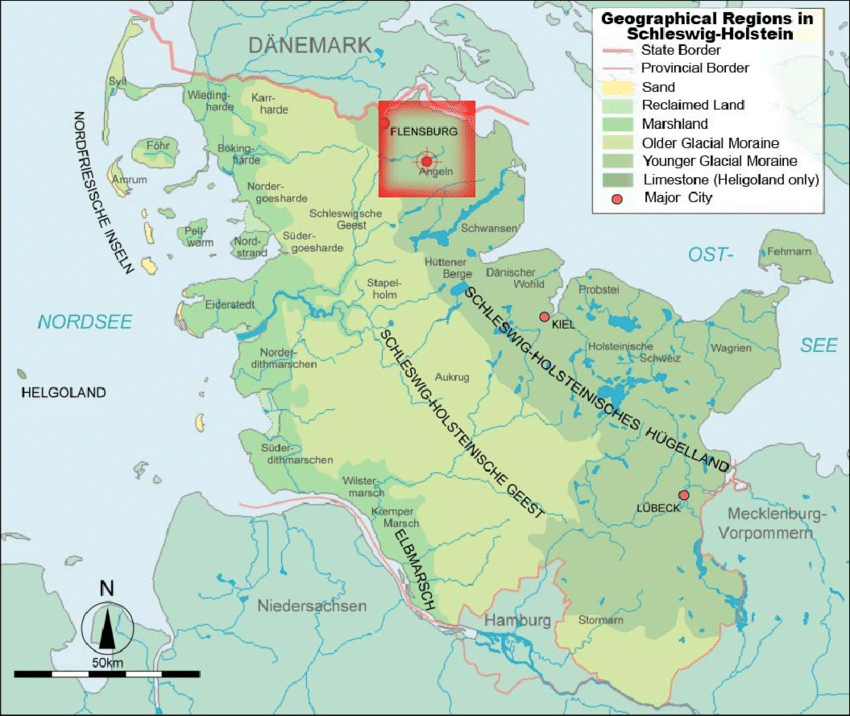

Schleswig-Holstein (Standard German), or Slaswik-Holstiinj (Northern Frisian), or Slesvig-Holsten (Danish), or Sleswig-Holsteen (Plattdeutsch); the eastern part of the German segment is the “highland”, elevated more than the sandy central and marshy west yet still gently hilly at best; Schleswig, the northern part, was contested through turmoil among the German elites and Danish commoners; after World War II, the border between Denmark and Germany was solidified, albeit a Danish minority remains at Flensburg – courtesy of ResearchGate

Holstein Switzerland Nature Park; as said, gently hilly at best – courtesy of AllTrails

Lübeck’s influence dispersed until the rise of the Hanseatic League as an official monetary-governing body. Hanse, which the league is called in Standard German, was a fellowship in the context of medieval mercantile guilds. The league itself was North Sea and Baltic Sea (port accessible, by direct sea or by river navigation) towns and cities functioning as a commercial and manufacturing amalgamation.

Courtesy of History Today

The Hanseatic League’s heyday was from the 13th century to the 15th. There are estimates the league survived, though lethally wounded and indirectly, to the 1700s, and by then other powerhouses took its place. Trade was east to west, from Novgorod to Reval, Riga, Visby, Danzig, Stralsund, Lübeck, and Hamburg; from Bruges to London it was based on item exchange from Northern and Eastern Europe for manufactured northwestern European items. Merchants supplementally traded items from Hanseatic cities themselves and advanced their wares to coastal hinterlands.

Until the 20th century, the Hanseatic League was envisioned as hostile towards credit, defined monetarily as “a contractual agreement in which a borrower receives a sum of money or something else of value and commits to repaying the lender later”. The alleged hostility would make the league backward, confounding historians as to how its economy even worked. Reemerging evidence and reevaluation finds the league wasn’t against credit, it utilized it counterintuitively by today’s credit standards.

What was the league’s Plattdeutsch connection? Middle Low German was the common language of Hanseatic merchants.

Mittelniederdeutsch

Middle Low German was another phase, after Old Saxon, for the Plattdeutsch family tree. MLG was the contemporary version of it from 1100 to 1500, and, as said, was the Hanseatic common language. MLG influenced North Sea and Baltic Sea languages, most noticeably the Scandinavian languages.

Courtesy of Nordregio

The Scandinavian languages, be they Norse or Finno-Ugric, weren’t unfamiliar with loanwords and conventions from southerly Germanic. Early Christian missionaries to Scandinavia were English and German. Old Norse helviti was ‘hell’, from Old Saxon helliwiti or Old English hellewite. Old Norse sál was ‘soul’, from Old English sāwol. East Scandinavian borrowed Old Saxon siala, later Danish sjæl and Swedish själ. Middle Low German’s influence was different since it was secular. The Hanseatic League’s common speech impacted the royal houses of Denmark and Sweden from 1250 to 1450. Low German speakers flooded Scandinavian towns and cities at the time, causing stock words and grammatical formatives to adjust the local languages. It was to Scandinavia what French was to England after the Norman invasions (that’s the reason, as YouTuber Langfocus observes, English’s structure is Germanic and vocabulary is closer to French, and that doesn’t even get to Latin’s influence on both).

Lost Status of Low German

Low German’s decline coincided with that of the Hanseatic League, dialing it back to the commoners.

The Christian Bible was translated to Low German in 1494 and 1522, then again by religious reformer Martin Luther in 1524. Luther was fluent in many German dialects, though largely central and northern. It’s why there’s a Low German translation of the New Testament based on his own translations of the Christian Bible from its original languages (Hebrew and Greek) to the language used in his political and social abodes.

Martin Luther’s proto-Standard German severed Low German’s prestige more. According to Langer, Nils, and Robert Langhanke, 19th and 20th century German education systems advanced its perception as a “yokel” communication. They say, “High German was considered the language of education, science, and national unity, [so] High German was seen as the best candidate for the language of instruction”.

Moreover, “regional languages and dialects were thought to limit the intellectual ability of their speakers. When historical linguists illustrated the archaic character of certain features and constructions of Low German, this was seen as a sign of its “backwardness””. Millions of northern Germans speak a Plattdeutsch variation, few for daily communication. More people speak it regularly in the Netherlands than in Germany. Revitalization initiatives are ongoing, but only time will tell if they’re fruitful.

Westphalian

Hochdeutsch’s hijacking of lingual importance in northern Germany knocked Plattdeutsch down many pegs. Even where Plattdeutsch is easier to find, it’s been impacted by Hochdeutsch and Dutch. An exception, relatively, is Westphalian. Westphalian is the furthest inland Low German, reaching the central German highlands. It borders the Central German continuums, which form the basis for Standard German, so Westphalian’s comparative lack of Hochdeutsch borrowings is even more impressive.

Dark red: South Westphalian; light red: the rest of Westphalian; blue: Northern Low German; yellow: Eastphalian; green: East Low German – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Besides Hochdeutsch’s broadly unsuccessful infiltration of the dialects, Westphalian stands out for its rising diphthongs. Diphthongs are monosyllabic speech sounds that begin at or near the articulatory position for one vowel and moves to or toward the position of another. For Westphalian, a sample rising diphthong is iäten ([ɪɛtn̩]) instead of etten or äten for “to eat”. Consonants within Westphalian vary from region to region. A sample is north of the Wiehengebirge (Wiehen Hills), people tend to speak unvoiced consonants, and south of the Wiehengebirge consonants are voiced.

Tracht (traditional clothing) from Münsterland, northern Westphalia – courtesy of Stadtmarketing Stadtlohn

Münsterland basin – courtesy of Planet Wissen

Sauerland, southern Westphalia – courtesy of Komoot

Mennonite Low German

A family of Low German speech is spoken outside Europe. It’s Plautdietsch. It’s spoken by some traditionalist Mennonites across the Americas.

Mennonites as a theological idea are nearly five centuries old, drawing from the sixteenth century Anabaptist movement. Anabaptists believe, for various doctrinal reasons, only adults committed to the faith are worthy of baptism, or symbolic acceptance by a congregation by water over their head.

Mennonites are named for Dutch theologian Menno Simons, though the denomination as it exists today began in Switzerland – same as the Alemannic Amish and near the Austro-Bavarian Hutterites (both Anabaptists). Nevertheless, many traditionalist Mennonites trace their ancestry to the Netherlands and northern Germany. It’s why some of them speak Low German. Note: Mennonite congregations are diverse ethnically and doctrinally, some abandoning Low German and modernizing by removing certain tenets. It’s why there are traditionalists and non-traditionalists.

1854 impression of Menno Simons – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Mennonites were reviled by Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and other Christians for reasons such as their pacifism, divergence from then-regularly-accepted religious practices and beliefs, and refusal to accept state-approved-and-sponsored religious attitudes. The last factor was a major no-no in German Lutheran lands, Martin Luther’s teachings emphasizing obedience to the state.

Mennonites fled westward to colonial America but didn’t speak Plautdietsch. That language was spoken by eastward-fleeing Mennonites. They went first to Prussia (no longer existent) before fleeing to Russia. The eastern flee caused these Mennonites to be surrounded by Slavic peoples, whose speech influenced Plautdietsch’s pronunciation and loanwords. Plautdietsch, in this way, can be thought of as a Christian edition of Yiddish; Yiddish, the language of many eastern European Jews, began as a medieval German dialect before its speakers fled east, likewise attaining Slavic-isms.

Thanks to Plautdietsch’s ties to Russia, the congregants who speak it in the Americas are known as Russian Mennonites to distinguish them from others. The Russian Orthodox Church followed the Catholic and Lutheran lead by persecuting Russian Mennonites for their religious beliefs. The Soviet Union persecuted Russian Mennonites for being religious at all. Persecution by ethnic Russians ensured Russian Mennonite flights to the U.S.A., Canada, and Latin America. Communities by these, and by Hutterites, are in many instances known as “colonies” for their self-sufficiency and limited contact with the cultures and societies surrounding them.

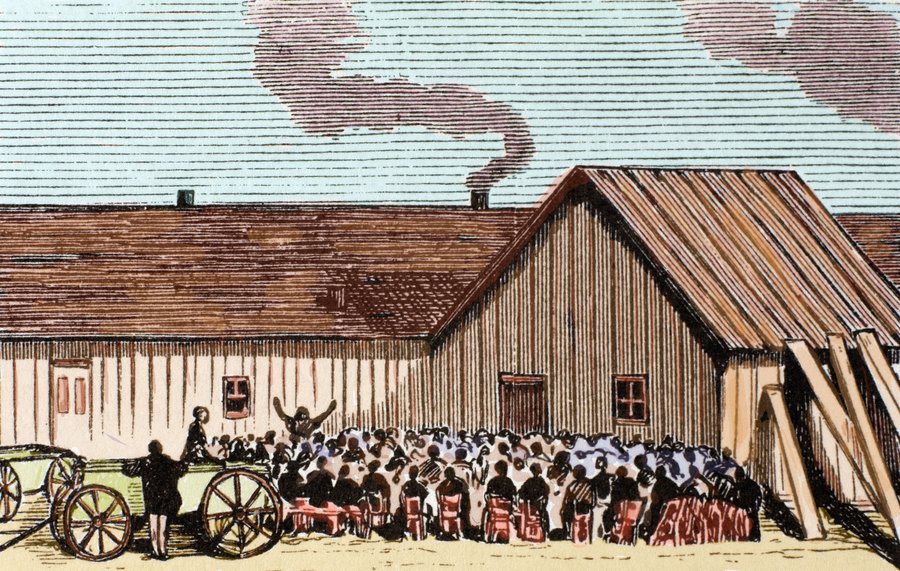

Illustration of Mennonites in Russia – courtesy of U.S.-Russia Relations

Belizean Mennonite colony – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Blog Authors in Relation to Low German

The matrilineal surname for this blog’s authors is Jansen. Readers of this blog may recall this lineage is directly from Rhineland-Palatinate in central Germany, but Jansen isn’t from central German.

House of Names says, “German surnames developed … when … most of the German provinces … were states of the Holy Roman Empire. At first people [were given or chose] a single name, but as the population grew and people began to travel, they began to find … an additional name to differentiate themselves [was required].”

In Schleswig, the northernmost German land, two of the common family name types are patronymic surnames, derived from the father’s given name, and metronymic surnames, derived from the mother’s given name. Jansen is from the personal names Jen, Jan, and Jon, all forms of John. In this sense, Jansen is a Low German/Dutch/German equivalent to the English “Johnson”. John is from the Hebrew name Johanan, meaning “Jehovah favored”. Jehovah, in Hebrew, means “God”, so Johanan and its spinoffs translate to “God’s favored”.

House of Names states, “The surname Jansen was first found in Holstein, where this family made important contributions toward the development of this district … Always prominent in social and political affairs, the family formed alliances with other families within the Feudal System and the nation. Although branches of this family are … found in the Netherlands and Denmark, German branches were distinct”.

German surnames, from standardized formats to local villages, abound in spelling variants. Jansen’s are: Jansen, Janssen, Jannsen, Jannssen, Janson, Jansson, Jansens, Janssens, Jannssens, Janzen, Jantzen, Janz, Jantz, Jans, Jaenz, Jaentz, Jaens, Jenz, Jentz, Jens, Jensen, Jenssen, Jensson, Jenzen, etc.

References:

- “High German vs. Low German: Understand the Differences”. Langster. https://langster.org/en/blog/high-german-vs-low-german-understand-the-differences/

- Owens, Robert L. “What is Plattdeutsch”. Worldwide Honkomp Genealogy. February 2003. https://www.honkomp.de/what-is-plattdeutsch/

- O’Keefe, Tadhg, Leggewie, Claus, et al. “Hanseatic League – an overview”. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/hanseatic-league

- Howard, Ebony and Clarine, Skylar. “Credit: What It Is and How It Works”. Investopedia. 1 October 2024 (Updated). https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/credit.asp

- “The origins”. Stadtebund Die Hanse. https://www.hanse.org/en/the-medieval-hanseatic-league/the-origins

- “Middle Low German”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Middle%20Low%20German

- Faarlund, Jan Terje, and Haugen, Einar. “Scandinavian languages”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Scandinavian-languages#ref603854

- “Low German New Testament”. SMU Libraries. https://bridwell.omeka.net/exhibits/show/highlightsreformation/lowgerman

- Langer, Nils and Robert Langhanke. “How to Deal with Non-Dominant Languages – Metalinguistic Discourses on Low German in the Nineteenth Century”. Linguistik Online. 12 June 2013. https://bop.unibe.ch/linguistik-online/article/view/240

- “About: Westphalian language”. DBpedia. https://dbpedia.org/page/Westphalian_language

- “Diphthong”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diphthong

- “Mennonites”. Oklahoma Historical Society. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=ME012

- “Jansen History, Family Crest & Coats of Arms”. House of Names. https://www.houseofnames.com/jansen-family-crest

- “Jehovah”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Jehovah