Courtesy of Outdooractive

These mountains are the visual signature of Bern Canton’s Lauterbrunnen valley. The Eiger is nearly four kilometers tall, the Mönch 4,107 meters, and the Jungfrau 4,158 meters tall.

Courtesy of Earth Trekkers

Physicality of Mountains Three

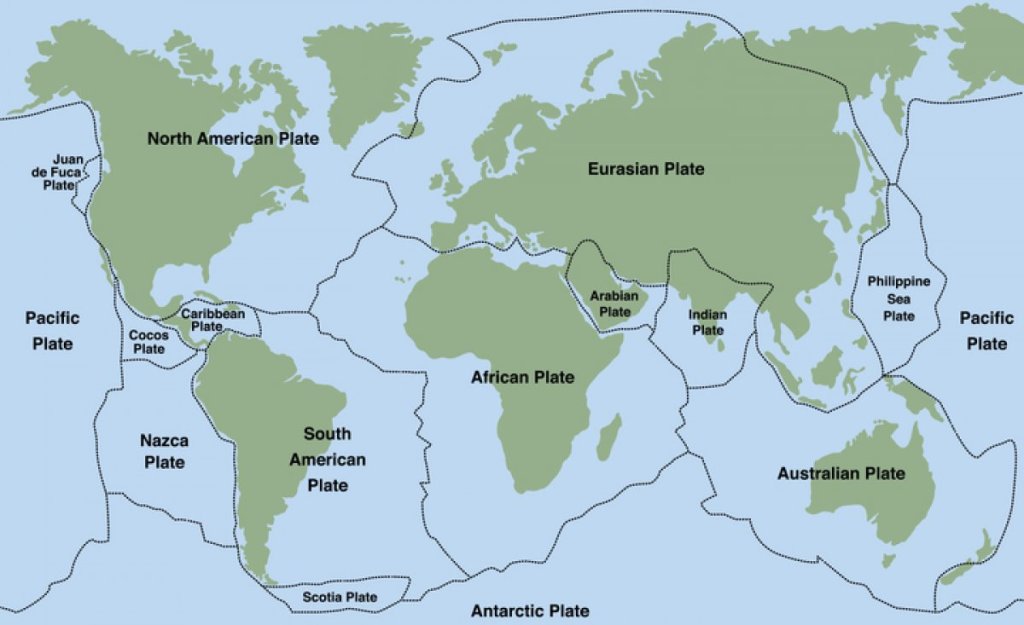

All three peaks were created 40 million to 20 million years ago by a collision of the African and Eurasian tectonic plates. Ever since, the Alps climb half a millimeter higher per year. Granites, gneisses, schists, amphibolites (oceanic crust sheathing continental crust) overlay already-existent carbonate sediments. Later erosion and glaciation carved the valleys. Mesozoic sediments are found in certain areas.

Courtesy of Newsweek

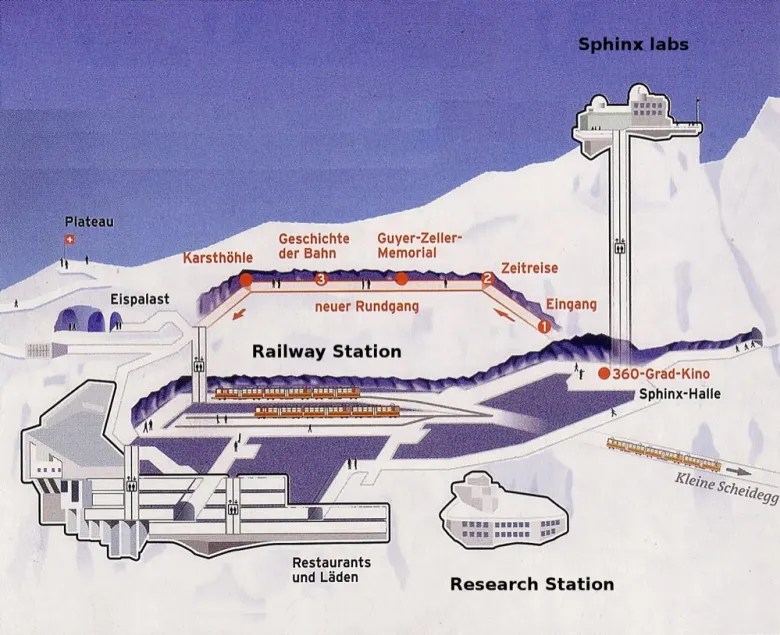

The height of the mountains – they aren’t called the “Top of Europe” for nothing – translates to an excellent location to measure European wind pollutants. The research station, at 1931 foundation a meteorology and astronomy observatory, continues to be a facility for climate study.

Courtesy of Daily Science

Courtesy of La Brújula Verde

In 2006, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Testing and Research reported increased levels of hydrofluorocarbons; these carbons were intended to replace the CFCs banned by the Montreal Protocol in 1989 due to their ozone layer damage. The source of the carbons was the Po Valley in Italy. Solar and cosmic ray research is ongoing.

Fluoromethane, a hydrofluorocarbon – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Courtesy of ResearchGate

Aletsch, at the three peaks, is the largest Alpine glacier (23 kilometers) and moves over 100 meters per year. Anthropogenic climate change, says the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, costs the glacier tens of ice meters, 2,855 total meters of its ice since the 1870s.

Aletsch glacier – courtesy of ESA Earth Online

Names of the Icy-Stony Flames of Fame

The Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau, in local dialect, translate to “Ogre”, “Monk”, and “Virgin”.

Illustration of the three peaks as literal versions of their name meanings (ogre, monk, and virgin) – courtesy of Jungfrau Region

The meanings of these may be older than Alemannic settlers’ perspective of the mountains. Eiger possibly began as the Latin “acer”, or sharp (referring to the mountain’s sharp north face), or the elder Germanic “ger”, spear or javelin. Mönch possibly referred to its pastures’ ownership by monks. Jungfrau possibly references a convent at the base of the mountain (the “Virgin Mary” idea and strict chastity among women are promoted by Roman Catholic doctrine).

Jungfrau Bahn

Adolf Guyer-Zeller was the son of a Swiss entrepreneur. Guyer-Zeller studied at Swiss, English, French, and American institutions. He returned to Switzerland to help his father’s business by expanding it and creating an export trade center in Zurich. More pertinently to this page, he invested in railways. His investing lead him to the presidency of the Swiss Northeastern Railway. By 1893, Guyer-Zeller envisioned the Jungfrau Railway.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The same year he envisioned the railway, Guyer-Zeller applied for a concession to build a railway from Kleine Scheidegg to the Jungfraujoch. The plan was to drill a tunnel through the Eiger and Mönch before constructing the railroad proper. He acquired the concession by 1894 and prepared the project. In a bid to make the rail entirely electric, Guyer-Zeller built hydroelectric power plants along nearby rivers. Construction began by 1896, a mostly Italian workforce tasked with physical labor. Many died.

Courtesy of Jungfrau

By 1898, the first open-air portion was finished. Guyer-Zeller envisioned adding a new station per year, but died in 1903. His sons oversaw the project from then. By 1905, the route reached 3,160 meters above sea level. Fund depletions caused the terminus to be the Jungfraujoch rather than the Jungfrau.

Courtesy of Jungfrau

By the project’s later years, disagreements, strikes, and accidents plagued it. By 1912, the last station, at Jungfraujoch, was finished. By February, the glacier was detonated through, and by August the Bahn’s official opening took place. Trips to the top station from the Eiger glacier began as over an hour, and today are 25 minutes from the same.

Courtesy of Berner Oberland Pass

References:

- Lubick, Naomi. “Travels in Geology: To the top of Europe: Jungfrau, Switzerland”. Earth Magazine. 12 June 2018. https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/travels-geology-top-europe-jungfrau-switzerland/

- Cage, Sam. “Names Shed Light on Storied Alps”. The Washington Post. 30 April 2006. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2006/04/30/names-shed-light-on-storied-alps-span-classbankheadfrom-jungfrau-to-eiger-many-peaks-owe-appellations-to-local-legendsspan/c76a2760-caf5-473a-948d-da5c59d2c19f/

- “A Brief History of Jungfrau Bahn”. ECHO Rails & Trails. https://echorails.com/blog/brief-history-of-jungfrau-bahn/