Courtesy of University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science Integration and Application Network

What Makes a Watershed

NOAA’s definition is “a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, streams, and rivers, and eventually to outflow points such as reservoirs, bays, and the ocean”. Watersheds range in size from a lake or county to thousands of square miles of water sources and waterways going hundreds of miles inland.

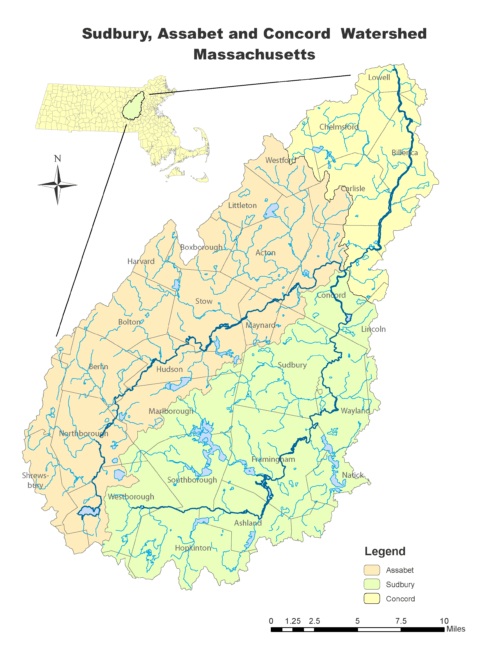

Massachusetts watersheds – courtesy of UMass Amherst

Watersheds are consistently set apart by ridges, hills, and mountains called drainage divides. The aquatic substances therein are surface water – lakes, streams, reservoirs, and wetlands – and all groundwater. Larger watersheds assemble many smaller watersheds.

Merrimack Watershed of New Hampshire and Massachusetts; SuAsCo southernmost subwatershed (green) – courtesy of USGS

Watersheds’ water flows from higher elevation to major water routes and eventually to places such as the sea; pollutants picked up along the way harm the waters and their destination. In scenarios where the water doesn’t flow to the sea, rain falls on dry ground and soaks into it. The soil groundwater seeps into the nearest stream, or collects deeper into the ground as aquifers (subterranean reservoirs). Areas with soils like hard clay are sparse in ground water, what water is there flowing to lower ground.

During blizzards and downpours, watersheds’ water intake may be so much that there’s few places for it to go. It could lead to the melting and flowing water running off and on human-made structures. The water collects in storm drains and floods waterways.

SuAsCo Glaciation and Glacial Lake Sudbury

The SuAsCo watershed was glaciated five times in accordance with the rest of the area, whose last glacial era was 10,000 years ago. The glaciers receded and left traces of their existence. Kettle ponds, made by detached ice blocks burying in outwash and melting to create earthen dips, were among them.

The landscape is flat save hills such as drumlins; these are elongated hills (made from clay, silt, gravel, and boulders) from where glacial margins were. Not all the SuAsCo hills are drumlins, however, i.e. Nobscot Hill in Sudbury and Framingham. The glaciation left shallow bedrock, so there’s limited groundwater resources that thankfully replenish consistently.

View from drumlin Cedar Hill summit, Northborough, MA – courtesy of AllTrails

Nobscot Hill – courtesy of Mountain Forecast

Glacial Lake Sudbury, named after the eponymous town, was a water body that was left behind by the ice sheets. Sudbury’s location is no stranger to glaciers, being pressed and turned by their movement for 2 million years, but Glacial Lake Sudbury’s glaciers are the only ones, within town boundaries, whose effects are viewable without intensive investigation (i.e. geology expeditions).

Yellow outlines are Minuteman National Historic Park – Courtesy of National Park Service

The lake itself was 4 miles wide, 20 miles long, and 90 feet deep. Nobscot Hill was perhaps the only spot that rose above the waters. A bedrock ridge and deltaic deposits dammed the southern outlet of the basin north of the lake, affecting Glacial Lake Concord (named after the eponymous town). Lake Sudbury washed away, leaving the Sudbury River valley and floodplain.

Sudbury River valley and floodplain – courtesy of Wicked Local

Logo of the Sudbury Valley Trustees, whose name is from the Sudbury River valley; SVT are custodians of multiple conservation lands across eastern Massachusetts, including a few in the town of Sudbury – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Swiftly Flows the Sudbury; Across the Assabet; Canoe the Concord

The Sudbury begins in Wesborough, going east and then north through Framingham, Wayland, Sudbury, and Lincoln until hitting the Assabet River in Concord to form the Concord River.

Native Americans lived in the SuAsCo watershed for thousands of years. Europeans arrived by the 1600s and pushed westward. Documents from Wayland’s history portray a time when river crossings used by Native Americans were used by British and British-descended colonists. The crossings built for foot traffic in their first forms, colonists widened them later for non-foot traffic travel. More Sudbury crossings were built to accommodate the burgeoning settler population.

Sudbury River at Wayland – courtesy of Town of Wayland

The Assabet River begins in Westborough, flowing north through towns like Berlin and Stow before conjuring the Concord with the Sudbury at Concord.

By the mid-1600s, the Assabet River was near Okommakamesit (Okkokonimesit), a settlement for Massachusetts’ “praying Indians”. The Natick Historical Society says these were Algonquian tribes, beginning in what is modern Natick (from local “a place of hills”, “my land”, “a corner”, or “a clearing”, from “nat” (“searching” or “seeking”) and “ick” (“a place”)), who converted to protestant denomination Puritanism at the behest of minister John Eliot. Native leader Waban and his 100 followers “established the new Christian village on fertile land north and south of the [Charles] river”. The village and other “praying Indian” settlements demanded “the Algonquian people … renounce their traditional way of life. They assented to living under English law and the Puritan religion. English-style agriculture … with … fenced-in farms worked by Algonquian men and women who lived in English-style and traditional “wetu” houses. Apple orchards were planted, and fish weirs (traps) were built on the banks of the river”. Gradually, “praying Indian” villages were seized by ethnic British settlers.

Okommakamesit (Okkokonimesit), whose ethnicity was Nipmuc (who lived towards the center of modern Massachusetts), as with other settlements like it, competed economically and otherwise with ethnic British Puritan encroaching settlements. By 1685, Okommakamesit (Okkokonimesit) was sold to colonial settlers. It and other lands around the Assabet River were homesteads, farms, and forests.

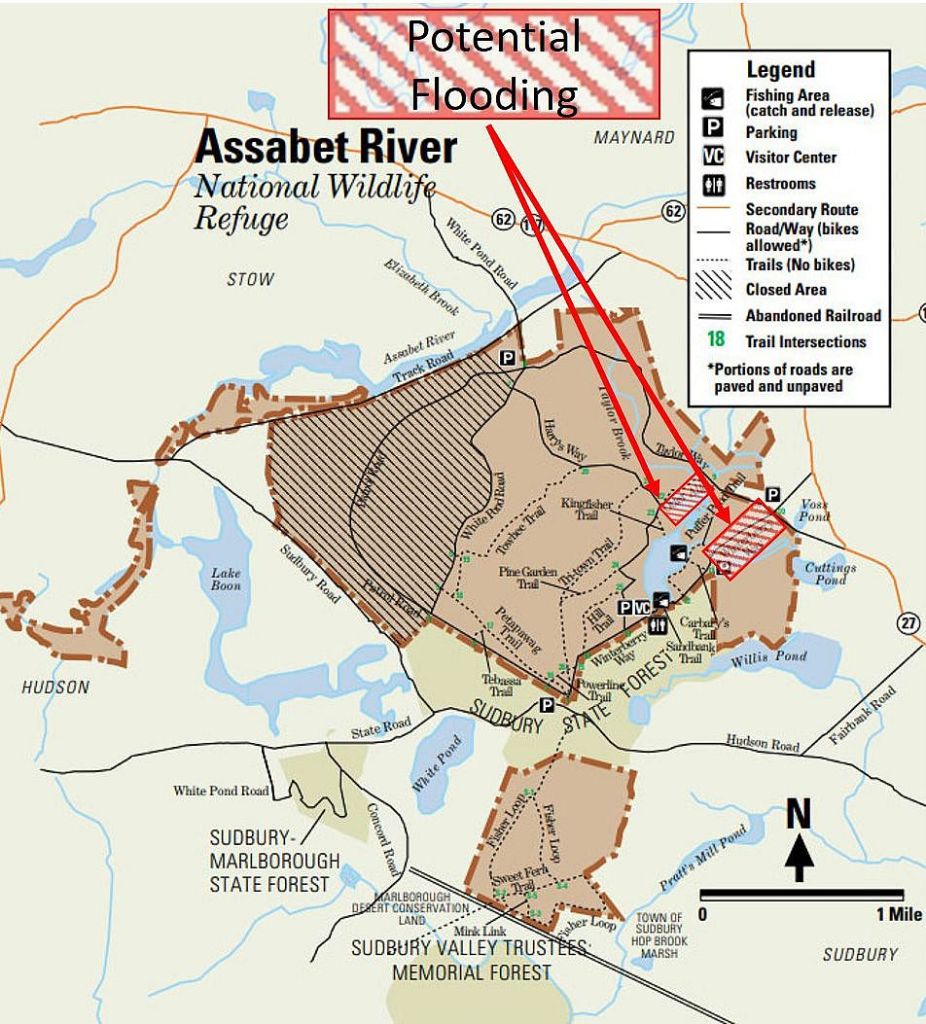

On a bank is a discontinued 2,230 acres U.S. military land. Military purpose lasting from the 1950s to the 1980s, the land switched to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ownership by 2000 to inaugurate the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge. By 2005, the refuge was open to the public. Traces of the military era for the refuge include things like the Cold War bunkers amid timbers.

Courtesy of Friends of Woodlands & Waters

Courtesy of Atlas Obscura

The Concord River begins at Concord, going north through towns like Carlisle and Chelmsford before at the city Lowell emptying to the Merrimack.

Concord River – courtesy of AllTrails

The town of Concord was, before colonial times, Musketaquid. Native Americans and Puritans utilized the Sudbury, Assabet, Concord, and tributaries for transport and food. By the 1630s, Puritans added water-powered mills and river hay feed for cattle. The area following Concord’s inauguration was deforested for agriculture. By the 19th century, financial intakes diversified away from farming.

Natu-Residents

Per the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System’s September 1996 report on the aquatic triad, they “and their floodplains support diverse … plants and wildlife in a variety of habitat[s] … ranging from open water through deep marsh, shallow marsh, scrub-shrub wetlands, and wooded swamps”. Complimenting this, “water storage … of these wetland[s] … in combination with” aquifers beneath the lands supports the rivers’ volume, thereby its plants and animals, even when the water is low.

Fish such as bluegill and pumpkinseed swim through the watershed; plants, native and invasive – such as purple loosestrife and glossy buckthorn – abound; and birds like blue heron fly across the land.

Bluegill – courtesy of iNaturalist

Pumpkinseed – courtesy of iNaturalist

Purple Loosestrife – courtesy of Tallgrass Restoration

Glossy buckthorn – courtesy of University of Minnesota Extension

Great Blue Heron – courtesy of iNaturalist

References:

- Dennison, Bill. “Environmental Literacy for the Assabet, Sudbury and Concord Rivers”. University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science Integration and Application Network. 19 March 2018. https://ian.umces.edu/blog/environmental-literacy-for-the-assabet-sudbury-and-concord-rivers/

- “What is a watershed?”. NOAA. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/watershed.html

- “Watersheds and Drainage Basins”. USGS. 8 June 2019. https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/watersheds-and-drainage-basins

- “Glacial Lake Shorelines”. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/view.htm?id=779F4BD2-7FCF-4052-BD8F-8C12EC8D0671

- “Setting the Post-Glacial Scene”. Town of Sudbury, MA. https://sudbury.ma.us/conservationcommission/setting-the-post-glacial-scene/

- “Crossing the Sudbury”. Wayland Museum. 10 June 2020. https://www.waylandmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Crossing-the-Sudbury-June-10-2020.pdf

- Mark, David. “Historic Assabet River Floods”. Maynard Memories: The Newsletter of the Maynard Historical Society. Issue 55. November/December 2010. https://maynardhistory.org/newsletter/MHS-MaynardMemories-NovDec2010.pdf

- “The Assabet River”. Massachusetts Rivers Alliance. https://www.massriversalliance.org/assabet-river

- “The First “Praying Indian” Village”. Natick Historical Society. https://www.natickhistoricalsociety.org/first-praying-indian-village

- “History of the Assabet River NWR”. Friends of Woodlands & Waters. https://www.woodlandsandwaters.org/assabet-river/history

- “The Concord River”. Massachusetts Rivers Alliance. https://www.massriversalliance.org/concord

- “Recreation on Concord’s Rivers in the 19th Century”. The Sudbury, Assabet and Concord Wild & Scenic River Stewardship Council. https://sudbury-assabet-concord.org/the-rivers/recreation-on-concords-rivers-in-the-19th-century.php

- “Sudbury, Assabet and Concord Wild and Scenic River Study”. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. https://www.rivers.gov/sites/rivers/files/2023-01/suasco-draft-study.pdf. Pages 18-20 . September 1996. Document found at “Sudbury, Assabet and Concord Rivers”. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. https://www.rivers.gov/river/sudbury-assabet-concord

- “Davis Farm Conservation Land”. Town of Sudbury. 12 November 2024 (revised). https://sudbury.ma.us/locations/davisland/

- “Memorial Forest”. Sudbury Valley Trustees. https://www.svtweb.org/properties/page/memorial-forest-sudbury

- “Jericho Town Forest”. Birding Hotspots. https://birdinghotspots.org/hotspot/L9385545

- “Mount Pisgah Conservation Area”. Sudbury Valley Trustees. https://www.svtweb.org/properties/page/mount-pisgah-conservation-area-berlin-and-northborough

- Molnar, Alexandra. “Mt. Pisgah Conservation Area reveals remnants of Northborough’s agricultural past”. Community Advocate. 6 October 2024. https://www.communityadvocate.com/2024/10/06/mt-pisgah-conservation-area-reveals-remnants-of-northboroughs-agricultural-past/

- “Village Story”. Village of Nagog Woods. https://www.villageofnagogwoods.com/village-story.html#:~:text=%E2%80%8BBrief%20History%20of%20%E2%80%9CLake,called%2C%20%E2%80%9CNagog%20Pond%E2%80%9D.