Ask someone in the United States of America what are cultural signifiers of Judaism, and you’ll be told bagels, dreidels, latkes (a potato pancake variety), Orthodox attire, and a slew of others. These are based in fact, but represent only the Ashkenazi Jewish ethno-sect.

Hanukkah is religiously insignificant in the grand picture of Rabbinic Judaism, or where the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and oral traditions are canon; the holiday celebrates the miracle of the oil for the Jerusalem Temple’s menorah (candle holder) being enough for an evening and keeping the candles lit for eight; this is why Hanukkah is alternately known as the Festival of Lights; Ashkenazim, the modernly dominant Jewish ethno-sect, put more emphasis on Hanukkah celebrations in response to Christmas; Hanukkah staples like dreidels (tops) are Ashkenazi innovations – courtesy of Peerspace

Chicago Orthodox Jewish congregation; Orthodox Judaism, the strictest form, began as an Ashkenazi movement – courtesy of The Times of Israel

Ashkenazi Jews’ title is a borrowing from the Hebrew “Ashkenaz”, initially referring to a nation bordering Armenia. In Medieval Europe, Ashkenaz was for theological reasons transplanted to the Rhineland of Germany and France. Throughout the centuries, Ashkenazi Jews encompassed those whose ethnoreligious (German) rite spread across northern, central, and eastern Europe.

Eastern European Ashkenazim – courtesy of Haaretz

Another Jewish ethno-sect are the Sephardim, from “Sepharad”, Hebrew for Spain. They aren’t as known as their Ashkenazi cousins. A shame, given they were “monarchs” of mainstream Jewish culture.

Spain, Not Plain

Jews lived in Spanish lands for over four centuries. The Sephardic golden era was considered Al-Andalus. Al-Andalus (711-1492 A.D.) was when much of the Iberian peninsula was the western frontier of the Islamic world. Iberian geography (the west of the Mediterranean and separation from the rest of Europe by the Pyrenees) isolated it from North Africa and Europe. Cultural separation was another isolation. The remoteness left Al-Andalus privileged in medieval myths whilst being noticed by Muslims and Christians elsewhere less consistently than you’d think.

Courtesy of Medieval and Early Modern Orients

Spanish Jews drew ideas and customs from Muslims and Christians. Arabic poetry was translated to Spanish and Greek. Hebrew texts were translated to Arabic. Arab melodies mingled with Jewish melodies. Muslim clothing was worn, except that forbidden to Jews (i.e. fur). It wasn’t all amicable. Jews, as elsewhere, were burdened with discrimination. During Al-Andalus, discrimination was from Christians and Muslims, rulers imposing things like requirements for Jewish males to wear yellow turbans late into Al-Andalus’ lifespan (bringing to mind National Socialists forcing Jews to wear yellow badges).

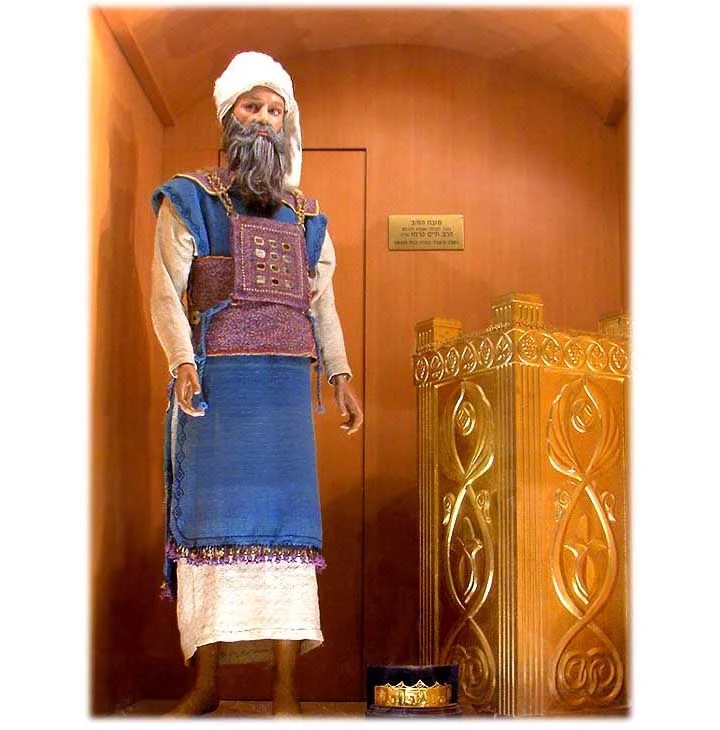

Andalusian Jewish worship; the headgear of the leader is modeled after those of Jewish religious leaders when the Jerusalem Temple stood – courtesy of Aish

Jerusalem Temple’s High Priest, Israeli museum reconstruction – courtesy of Jerusalem Chronicles

Discrimination stacked against Sephardim irrespective of their societal familiarity, Spanish Jews flourished through it all. Intellectual and spiritual accomplishments defined Andalusian Jewish writers, poets, philosophers, and courtiers. Medieval Spain introduced Jewish thinkers who continue to be studied in Jewish and non-Jewish academia. Ibn Ezra, Ibn Gabirol, Judah Halevi, and Moses Maimonides (the Rambam) were all Sephardi.

Ibn Ezra illustration – courtesy of Rabbi Jay Asher LeVine

Statues of Ibn Gabirol and Judah Halevi – courtesy of Aurora Israel

Statue of Moses Maimonides (the Rambam) – courtesy of The Huffington Post

Spain in the Neck

Christians reclaimed Toledo, Spain from Muslim rule by 1098. Thus began the slow decline of Jewish influence in Spanish societies (coinciding with Muslim rulers gradually losing power over Iberia) until 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella evicted Jews who refused to convert to Christianity.

Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain – courtesy of Sites at Penn State

The Spanish Inquisition, a collaboration by the Roman Catholic Church and secular Spanish politicians, targeted “heretics” and non-Christians; anti Judaism continued in the Spanish Empire after; depicted is the Mexican Inquisition, also targeting Jews – courtesy of The Times of Israel

Spanish Jews who converted to Christianity were known as Marranos. Those among them who were “crypto-Jews” secretly continued the Sephardi rite. Some Sephardim settled in Portugal until dangers there forced them to convert by 1497. Sephardim also fled to the Ottoman Empire (especially Greece and Turkey), where they spoke Ladino. Ladino was to these Sephardim what Yiddish was to eastern European Ashkenazim: a medieval dialect of a language (Spanish for Ladino, German for Yiddish) peppered with Hebrew and local lingual loanwords. Yiddish thrives today among Orthodox Jews, but Ladino isn’t as fortunate. Its speaker numbers are shrinking wherever it’s spoken (Latin America and Israel).

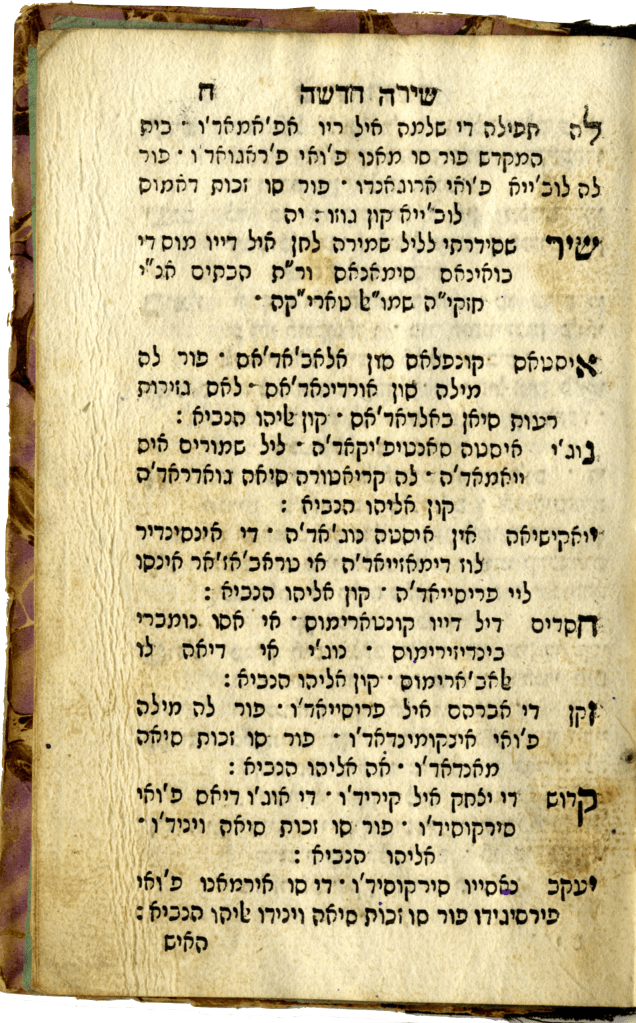

Ladino sheet music – courtesy of University of Washington Sephardic Studies Program in the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies

North African and Ottoman Sephardi communities could be open about their faith at the cost of second class status. Sephardi congregations appeared in the Netherlands, the Balkans, Italy, Syria, Palestine, Brazil, New York, and Latin America.

Baruch Spinoza (center), of the Amsterdam (Netherlands) Portuguese Jewish community, is seen with hesitation and derision by fellow Jews in this 1907 Samuel Hirszenberg painting; the work references Spinoza’s exile from his own Jewish community for his beliefs and opposition to rabbinic authority (reenforced by a congregation member in the picture reaching for a loose stone, implicitly to throw at Spinoza); Spinoza, like Maimonides before him, is studied academically by Jews and non-Jews – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Sephardim who went to the Middle East met culturally and matrimonially with Mizrahim, or Jews who never left the region. In the 19th century, the Sassoons, a merchant family centered in Baghdad, held business stakes from there to Shanghai to Mumbai to London. Leader David Sassoon began as treasurer to a Baghdad official; he was a successful Mumbai trader following Ottoman Iraq’s eviction of its Jews. David supported relief for Iraq’s poorest Jews.

The Sassoons were a Middle Eastern Jewish family who were of Sephardi extraction – courtesy of Off-Piste Investing

Before World War II and the Holocaust, European Sephardim were plentiful in Greece, Yugoslavia (now divided into multiple nations), and Bulgaria. Jewish communities in Serbia and northern Greece were subjugated by German invaders in April 1941. These Jews suffered degradation, forced labor, etc. before being deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered from March 1943 to August 1943.

Southern Greek Sephardim were subjugated by Italians, who refrained from anti-Jewish legislation and held off on deporting Jews to German-ruled regions until Italy’s 8 September 1943 surrender. From there, these Jews were at the nonexistent mercy of the Germans.

Bosnian and Croatian Sephardim were ruled by a German-backed Nazi-Catholic satellite state in April 1941. Pogroms were enacted before the Croatian supremacist Ustasa sent Bosnian and Croatian Jews to camps, where they were murdered alongside Serbs and Roma.

Macedonian and Thracian Sephardim were subjugated by Bulgarian occupiers, who turned them to the Germans. Sephardim of Bulgaria itself were tormented by a National Socialist-allied government. They were saved from execution, however, by Bulgar parliamentarians, clerics, and intellectuals.

The State of Israel’s foundation in 1948 was met with Muslim nations evicting their Jewish populations, including Sephardim. Owing to Israel being an Ashkenazi-founded state (and Sephardim and Ashkenazim’s historically tense relations), Sephardi Jews found it difficult to be educated, elevate out of poverty, and enter the state’s economy. Civil rights movements in Israel reversed Sephardi misfortunes, though Sephardim still face discrimination and prejudice even as Jewish ethno-sect intermarriage blooms.

In the 21st century, there are 138 Sephardi congregations across 21 U.S. states. Sephardim are known among those who know them for their warmth and generosity.

Sephardi vs. Ashkenazi

Ashkenazim and Sephardim share Middle Eastern and European beginning backgrounds (the source of their European ancestry from different locations) and, more importantly, religious customs. Whereas at some time Ashkenazim and Sephardim clung to near-identical beliefs, the diversion appeared to begin at 1000 A.D. That year was when Rabbi Gershom ben Judah struck down a polygamy endorsement accepted by Ashkenazim and rejected by Sephardim.

Jewish rites and associated ethnic assemblies globally; the “Land of Original Israelites” is partially incorrect since it goes to eastern Jordan – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Sephardim and Ashkenazim follow the same halakhah, or Jewish law, though somewhat differently. Pesach (Passover) sees Sephardi Jews eat rice, beans, and other foods Ashkenazi Jews avoid at this time. Observance of and agreement with traditions differs among all Jews, but Sephardim aren’t formally organized into different movements. Ashkenazim, alternatively, are classically on a spectrum from Reform (least stringent) to Orthodox (especially stringent).

Spanish rite and German rite differ on pronunciation of certain Hebrew vowels and a Hebrew consonant. German rite is increasingly accepting Spanish rite pronunciation in the wake of its popularity in 1948 founded Israel. Sephardi worship sessions are somewhat different from those their Ashkenazi cousins embrace (down to the melodies). Holiday foods and general cultural foods differ as well. I.e. both ethno-sects eat fried foods at Hanukkah in memory of its miracle; Ashkenazim eat latkes (German rite potato pancakes) and Sephardim eat sufganiot (Spanish rite jelly doughnuts).

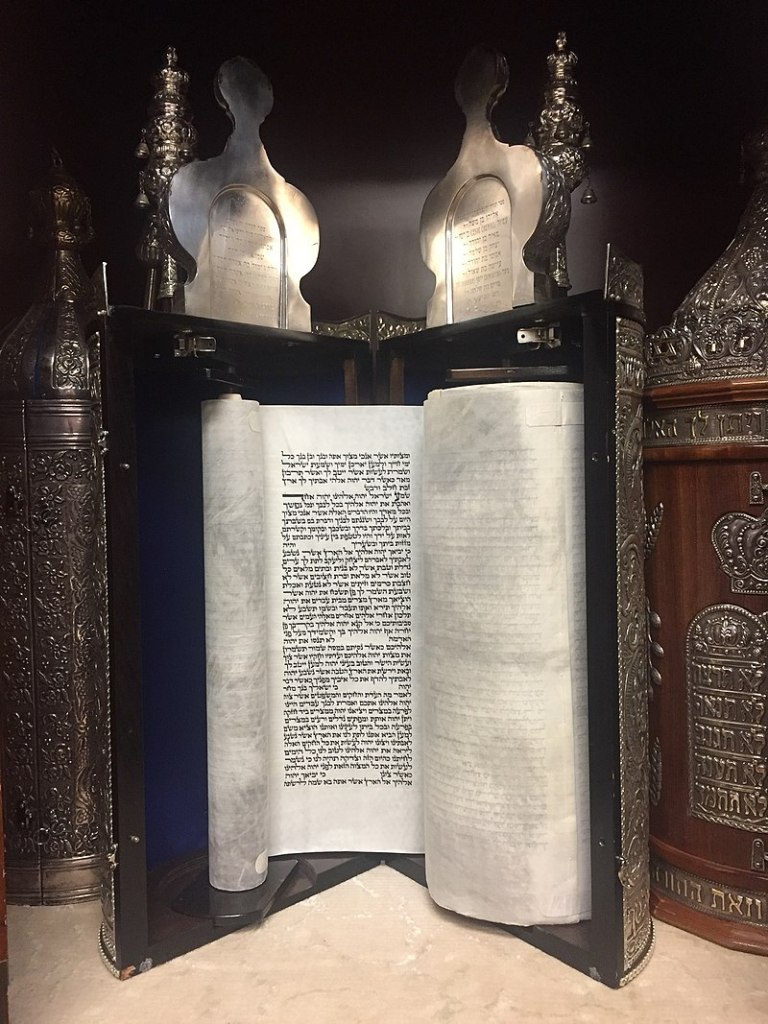

Ashkenazi Torah scroll; traditionally sheathed in fabric outside worship – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Sephardi Torah scroll; casing closed outside worship – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Traditional Ashkenazi synagogue; this is similar to European churches, where the focus is on the ritual station towards the back – courtesy of Samuel Gruber’s Jewish Art & Monuments

Traditional Sephardi synagogue; Spanish rite closeness to the Middle East equals the ritual station being at the center – courtesy of TimeOut

Defining Difference?

The arguably largest difference between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews is their attitude to the Gentile world throughout history.

Ashkenazim lived in Christian Europe, where tensions between the faiths was overwhelming. German rite Jews isolated from their neighbors by choice or by necessity. Sephardim lived in the Islamic world, where, though oppression wasn’t unheard of, there was comparatively less of it and segregation. Sephardim were regularly more integrated locally than Ashkenazim. It was what allowed Spanish rite Judaism to be influenced by Arabic and Greek philosophy and science.

David Shasha, Director of the Center for Sephardic Heritage, explains this was more meaningful to Rabbinic Jewish life than it appears.

He quotes scholar Zvi Zohar: “Who best embodies Judaism’s religious-cultural ideal-type: the individual who … immerses himself in … study of Jewish texts and traditions, or … one who combines command of Jewish texts and traditions with serious knowledge and a fundamentally positive evaluation of … ”general” culture? In … the 11th and 12th centuries … Ashkenazic Jewry … identified the first type … whereas Sephardic Jewry espoused the second “.

Medieval depiction of an Ashkenazi Jew, here wearing a conical hat worn early on optionally but forced upon Jews by later church and secular law, conversing with local German authorities – courtesy of My Jewish Learning

Medieval Sephardi Jews at a game of chess – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Zohar, continuing, “After the expulsion from Spain and the Sephardic cultural renaissance of the 16th century … involvement of Sephardic rabbinic intellectuals in ”general” culture [was] more limited … Nevertheless, the classical Sephardic model … retained its viability, at least as a latent cultural option, and sometimes as more than that. Thus, when political, social and cultural changes … during the 19th and 20th centuries enabled realization of aspects of the classical model, Sephardic rabbis advocated it”.

Sephardi Jews, with reason, saw themselves as Jewish nobility. Sephardi culture was a religion science synthesis named by Shasha as “Religious Humanism”.

Back to Zohar, Shasha says, “even as … modernity … eroded the efficacy of the old Andalusian model under the pressures imposed by the Ashkenazi ascendance … this model continued to [be for Judaism] a … beacon to a … more sophisticated understanding of its traditions”.

The ethno-divisions’ shared Levantine ancestry and religion didn’t equate to peaceful relations between them. Disagreements appeared over doctrine and ceremony, among other topics.

David Shasha quotes James Picciotto’s 1865 book “Sketches of Anglo-Jewish History”: “The original [Jewish] immigrants … to England from [Central and Eastern Europe] were … at a … disadvantage as regards the Spanish and Portuguese settlers … usually … of wealth … of old lineage, whose ancestors … figured at courts, and who in modern times … constituted an aristocracy of commerce in [the Netherlands]. The former were persons whose forefathers … [were] subjected to … degrading persecution, and … debarred from pursuing … ennobling avocations; persons who themselves [were] neither … endowed by their fathers with worldly goods [nor] with liberal knowledge”.

James Picciotto was from a Sephardi family esteemed as Euro Mediterranean diplomats and financiers, so he was amongst the most qualified to speak about the Ashkenazi vs. Sephardi conflict. Shasha quotes Picciotto again, this time about the 18th century regularity of Sephardi community leadership demotions for marrying Ashkenazi Jews.

He goes: “Jacob Israel Bernal was a … West India merchant … from … honorable stock, though not ranking in the first line of Hebrew capitalists. In 1744 he was elected to the Synagogue office of Gabay (Treasurer), but … he resigned his functions … the following year. When the reason of this act became apparent, the astonishment of the elders … increased. Jacob Israel Bernal … applied to marry a German Jewess. For a member of the Portuguese Congregation … [it] was an unexampled occurrence, upon which the Mahamad [Synagogue council] could not venture to pronounce an opinion!”.

The mentioned Ashkenazi ascendance brought issues of its own. Shasha says, “For all the fractiousness and infighting that … takes place in the Jewish world, the vast majority of those whose voices are heard so loudly and often piercingly in the discourse are closely united by their history and culture, a history that begins and ends in the Shtetls of Europe”. Shtetls were where eastern European Jewish life took place; the majority of these villages’ populations were Jewish, with Gentiles as minorities. As other parts of Europe, Jews encountered hostility and violence from outside their communities, in the worst cases erupting into pogroms. Shtetl life was routinely involuntarily nomadic.

Shasha’s opinion is, “The Sephardic ideal … always … understood in terms of political moderation and community unity. Rarely did Sephardim lose … internal cohesion … until … cultural erosion set in”.

Shasha laments, “Following the Ashkenazi lead, Sephardim abandoned their traditional culture and adapted to the fractious Ashkenazi model … the Sephardi particularity … its cultural genius and sophisticated social mores … a lost value. The Ashkenazi culture … its deeply unsettled relation … to the larger world … the Jewish standard”.

References:

- Schoenberg, Shira. “Ashkenazim”. Jewish Virtual Library. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ashkenazim

- “Who are the Sephardim?”. Magen David Sephardic Congregation – Beit Eliahu Synagogue. https://www.magendavidsephardic.org/who-are-the-sephardim.html

- “Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/met-publications/al-andalus-the-art-of-islamic-spain

- “Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews”. Judaism 101. https://www.jewfaq.org/ashkenazic_and_sephardic

- “Sephardi Jews During the Holocaust”. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/sephardi-jews-during-the-holocaust

- Shasha, David. “Understanding the Sephardi-Ashkenazi Split”. The Huffington Post. 20 June 2010 (Publication), 25 May 2011 (Revision). https://www.huffpost.com/entry/understanding-the-sephard_b_541033