Attention (as they say in standard French): the Loire Valley extends east to west from significantly inland all the way to the Gulf of Biscay; the river its named after gets its water sources (in its own watershed) from a larger area still; the map shown centralizes on the central Loire valley – courtesy of European Waterways

Courtesy of kimkim

For our 2024 trip to Europe, our first visits were medieval chateaus in France’s Loire Valley. Chateaus, as defined by Merriam-Webster, are “a feudal castle or fortress in France … a large country house … a French vineyard estate”. Traditionally, these were equivalent to modern “summer homes”, traveled to seasonally (often summer) to enjoy different areas for their weather, terrain, etc. For French royalty, chateaus at the Loire and elsewhere were retreats to where they could relax, hunt, etc. What else is there?

Water and Stone

It’s believed the Colorado river and the Grand Canyon formed when multiple different rivers collided as the Colorado plateau lifted. The same is believed to be true for the Loire river valley.

During the Paris Basin’s formation and lift, the “paleolithic Loire”, one of the two rivers that turned into the Loire as it is today, flowed north to the Seine river (that famously flows through the city of Paris). The “second Loire” flowed west from the Giennois region at about the same as today’s Loire.

Seine river at Paris; the blog authors, their immediate family, and others say the Eiffel Tower and Paris in general are just as amazing, if not more amazing, in the evening – courtesy of Avalon Waterways

Courtesy of Groundwater Project books

As the Paris Basin formed, “Giennois Loire” absorbed “paleolithic Loire” to assemble the modern Loire river valley. As for the riverbed where “paleolithic Loire” went to the Seine, it’s where the Seine tributary Loing is.

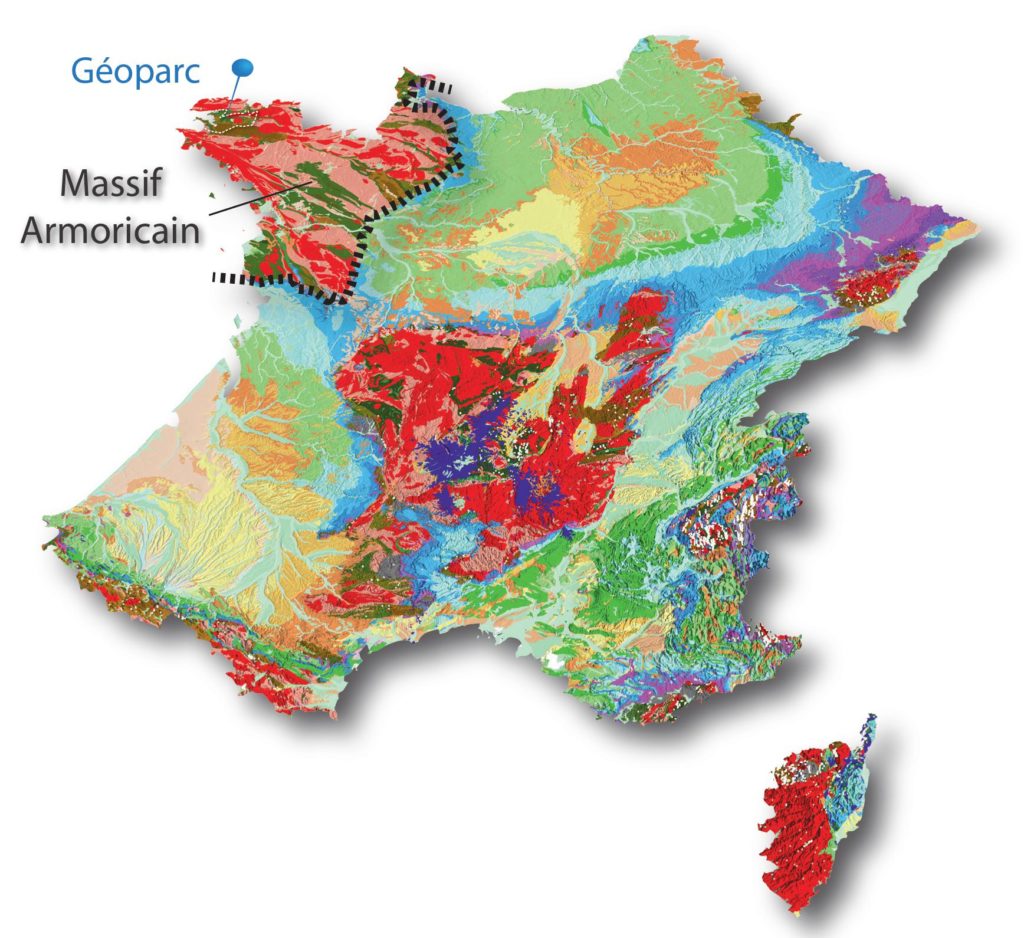

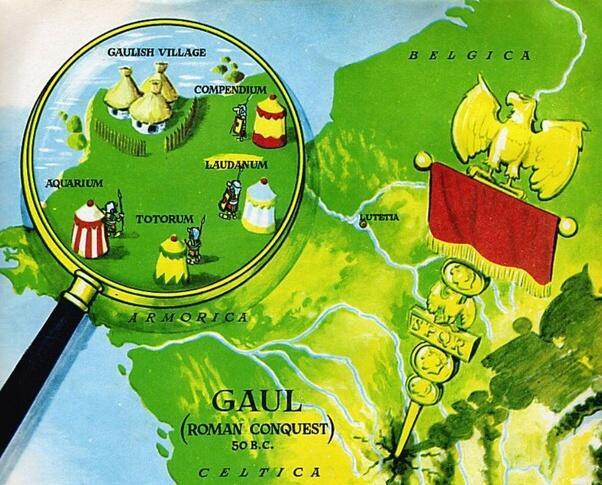

Modern Loire flows through three major geologic regions: Massif Central where it begins, flowing north to Paris Basin, and into Massif Armoricain. About Massif Armoricain: it refers to the Latin name for the region, Armorica, in the Ancient Roman era a region noted for its Celtic culture. Brittany, where Armorica was, retained its Celtic culture against the rest of France alright … except, its language and culture isn’t technically mainland Celtic. The “original” Brittany Celtic culture went extinct after Gallic Latin and French superseded local culture and languages. Celtic culture was revived in Brittany after a Brittonic Celtic tribe fled across the English Channel. On the other side, their culture in time was the regional identity of Brittany, itself named after those fleeing Brittonic Celts.

Massif Central – courtesy of Blue Green Atlas

Massif Armoricain, west of Paris Basin, itself north of Massif Central, for reference as to modern Loire’s flow route – courtesy of Geopark Armorique

Armorican Celticness was referenced not only by Ancient Romans but by French later on; Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, respectively original writer and original artist for the Asterix comic series, outright said many of the adventures of the titular Gallic Celt and his friends began at Armorica (that is where Asterix and his closest allies live); Asterix’s series is recommended reading, though be advised many jokes require knowledge of Ancient Roman, Ancient Greek, etc. history and, being a series begun in the mid 1900s (indeed, it’s so popular it gets new issues into modern times; there’s even merchandise and a French theme park competitor to (likewise recommended) Disneyland Paris), elements of it are products of their time – courtesy of RFI

In addition to the three geological regions, the river itself is divided into three areas. Upper Loire is the southern zone, from the river’s source to where the Allier joins the Loire, more a highland stream than a river. Middle Loire is from Allier’s confluence to where the Maine joins the Loire. Here is where the valley’s famed chateaus are most found. Lower Loire is from Maine’s confluence to an estuary at the end of the aquatic trail to the Atlantic.

Courtesy of Odyssey Traveller

Volcanic Mont Gerbier de Jonc, at Ardèche region, is where modern Loire begins. An aquifer below the mountain flows often due to the area’s high water table, surfacing as three springs. These springs converge further down the valley, creating a stream that, over 629 miles, transforms into a river. At 50,000 square miles during its north and west travel, the Loire is France’s longest river.

Loire is claimed to be Europe’s last “wild river”, no dams are along its main course. It is no longer easily travelled, instead shallow; the French government is trying to destroy its tributaries’ dams to raise the Loire’s water level. Hinting at it working, river trout, eel, wild boar, and deer are seen again in the water and along its banks.

Ancien Histoire de la Loire

During the Iron Age, Cisalpine Gallic Celts the Cenomani lived at the Loire valley. By 52 BC, Ancient Romans led by Julius Caesar took over the valley and much of the rest of Gaul. Celtic villages were replaced by places like Orleans (namesake of America’s New Orleans). Baths, forums, theaters, and vineyards were built. By the 4th century A.D., Loire residents converted to Christianity.

By 451, Attila the Hun’s forces swept across Europe and attacked places likes France, including the Loire valley. Roman forces defeated the Huns, only to be usurped by the Clovis’ troops. Clovis’ reign is regarded as modern France’s identity establishment. Louis, from his name, was a regular name for French kings.

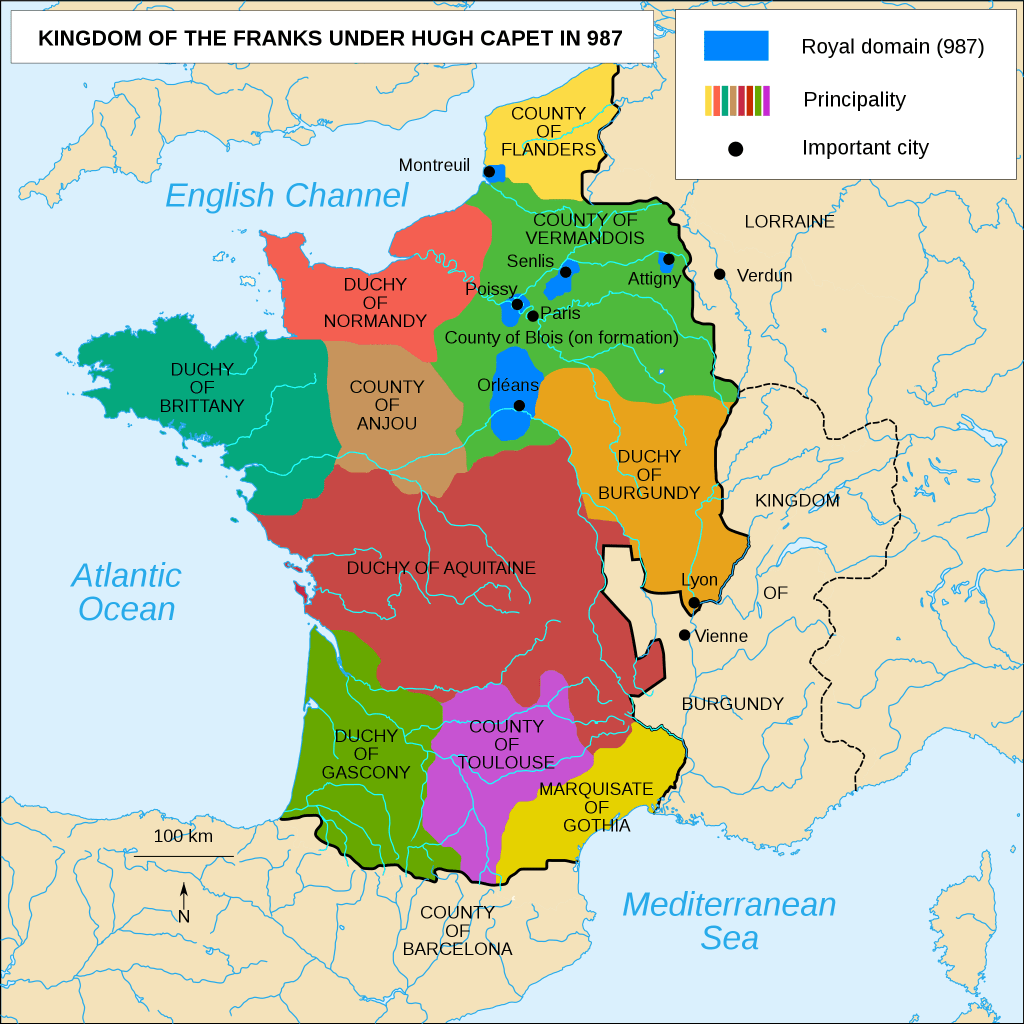

France, though by then not as fragmented as its German neighbors were, was authoritatively decentralized. Loire’s rulers’ authority rivalled that of French kings, albeit the Roman Catholic Church’s larger de facto power resulted in Loire royals more often heeding the Church’s advice about disputes.

Courtesy of Medieval Reporter

The Loire valley was a territory claimed by Charlamagne. His sons, after his 814 A.D. demise, inherited his land and created from them Anjou and Blois. Anjou’s count Henry Platagenet, who additionally reigned Normandy and Aquitane, invaded England to be King Henry II in 1154. This was a problem. England claimed the Loire valley and the French Crown despite its rulers and residents living on an island unconnected to mainland France.

More problems were on the horizon in the form of the Hundred Years’ War.

1337 to 1453: English House Plantagenet battled French House Valois.

According to Odyssey Traveller, “duchy of Guyenne (or Aquitaine) belonged to … kings of England but remained a fiefdom of the French crown, and … English kings wanted exclusive ownership … as the closest relatives of the last direct king of the House of Capet (Charles IV, who died in 1328), the kings of England from 1337 claimed the crown of France … Charles IV [and his spouse conceived] a daughter, but as females were denied succession to the French throne … House … Capet ended. England’s Edward III, son of Charles IV’s sister Isabella, was Charles’s closest male relative by blood, but … French nobility ruled … Isabella, who herself did not possess the right to inherit, could not transmit this right to her son. Charles IV was succeeded by his cousin Philip who belonged to … House … Valois, [itself] embroiled in the long war with Edward III and the succeeding English kings”.

England’s siege of Orelans transformed the Loire valley into a Hundred Years’ War focus. Joan of Arc’s campaigns led to the removal of Orleans’ siege in 1429 and King Charles VII’s coronation (by 1431, Joan was captured by English ally Burgundy and martyred). Joan’s victory assisted French troops’ morale and led to later French reclamation of English seized territories.

Francois I and successive nobility built the Loire’s famous chateaus, one, Chateau de Chambord, Francois I himself lived at.

Chateau de Chambord – courtesy of Orléans Val de Loire Tourisme

By the 15th century, France’s invasion of Italy and contact with the latter’s art and architecture initiated the French Renaissance. To French dismay, “beauty and developments brought by the French Renaissance [were alongside] violent religious wars between … Protestants and Catholics”.

Dark red areas are where Huguenots were gathered in native France; they later fled persecution to Protestant friendly areas of Europe – courtesy of Musée protestant

Huguenots, French Protestant converts, saw their toleration by Catholics turn to hatred towards them by 1572. Another temporary peace vanished when Huguenot Henry of Navarre was heir to the French throne by 1584. The War of the Three Henrys, of Navarre, King Henry III, and Roman Catholic Henri I, broke out. It ended when Henry III before death acknowledged Henry of Navarre as his heir. Catholic French, with Spanish forces, opposed Henry III’s rule until his conversion to Roman Catholicism. He was crowned Henry IV, and created 1598’s Edict of Nantes, guaranteeing religious liberty to French Protestants, hereby ending that era and nation’s religious wars.

Artist impression of Henry IV – courtesy of Encyclopedia Britannica

After the edict, the Loire valley was a stalwart agriculture and textile industry area. A “weakened French monarchy shift[ing] its political focus from Loire to Paris, [led] to the decline of the region”. By 1789, the French Revolution toppled the monarchy.

By the 1940s Loire was, like the rest of France, shackled by invading Germans. Many chateaux and regional features were demolished.

Days on the Claise says about La Roche Posay, a town notably affected, “The Nazi officer in charge of German troops in [the] area was the notorious Brigadier General Botho Elster, who is known to be directly responsible for a number of atrocities. On Sunday 27 August 1944 a German column led by Elster took 60 people hostage in La Roche Posay”.

“After the Allied landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944, and … in Provence on 15 August, the German army [went] towards the East and crossed the Touraine, south of the Loire … Several thousand Indians … enlisted with the Germans, due to dissatisfaction with the British, and with the Germans … were … encouraged to spread fear amongst the population … they … are reported as entering and occupying private homes and at times chasing down women [other page spells it out yet readers here should know implication behind wording] … enemy troops engaged in stealing bicycles, carts and horses, burning houses and shooting local men”.

The baffling scenario, a minority of Indians helping National Socialists, mirrors what happened among a minority of Irish during World War II. Those Irish collaborated with Nazis to spite England for their centuries of oppressive rule. A different motive: “an element of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was convinced that a German victory could end the British “toehold” of Northern Ireland and bring about a united nation”. Irish and Indians were rightfully angry at what English and their allies inflicted upon them. That aside, there were better options than working with Germans just because they opposed England during World War 2, most Irish and Indians went for those. There’s no excuse for participating and complicity in war crimes and allying with regimes promoting supremacism.

In August 1944, “it was announced that a German column was [marching] towards [La Roche Posay]. Everyone knew about the recent tragic events of Oradour sur Glane, where … occupants were massacred … the town burned. Some inhabitants of La Roche Posay left … With the approach of the column along the Pleumartin road, about 6 pm in the evening, anyone remaining barricaded themselves inside, shutters slammed, and doors locked. Children were sent … to the cellars. When the Germans arrived the cowering people could hear, out in the street, orders shouted, rifle butts beating on the doors, windows being broken. Two German soldiers with a hostage came seeking the ‘Burgmeister’. The mayor, Robert Nonnet, immediately realised that they were there for him, and bravely went out to meet them, leaving his … sons hiding in their cellar”.

Prior to La Roche Posay, “the German column was attacked by some French Forces of the Interior (FFI) Resistance fighters … Germans burned the nearest farm. They were by then very nervous, and feared further attacks by the Resistance, so they made threats to the local populace … German soldiers … thought … to get across the bridge over the River Creuse at La Roche Posay, then the bridge over the Claise at Preuilly-sur-Claise (where I live), fleeing north … they feared that the Resistance would destroy the bridges and block their flight, leaving them at risk of being massacred”.

“Father Brand, chaplain of the Herriot School … managed … a deal with the German Commandant: to contact the Resistance and convince them not to attempt any action in the night and not to destroy the bridge at Preuilly, otherwise the hostages would be executed. Father Brand [met] Georges Butruille, one of the leaders of local Resistance, who accepted the deal. He was next brought to an isolated farm where he remained hidden. At La Roche-Posay, the hostages, after questioning, were freed. The mayor saved their lives by vowing that there were no maquisards or FFI among them, which was untrue. The mayor of Preuilly equally put his own life on the line by promising that the Germans would not be subject to guerrilla attacks as they passed through his jurisdiction. The soldiers of the Elster Column finally left La Roche-Posay, but not without looting houses and having killed a young Resistance fighter from Yzeures sur Creuse, Jacques Martin … They were finally stopped not very far away … the Germans [fought] their way through [a] village … made it to Beaugency, where the leaders of the French Resistance and the American Airforce General Macon [got them to] surrender … 17 September, on the bridge over the Loire”.

By the 1960s the Loire crawled back to prominence by opening its chateaux to advance a tourist industry.

300 chateaux exist in the Loire, the valley between Sully sur Loire and Chalonnes a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2000.

Exemples de Châteaux

Describing every Loire chateaux is a daunting task, so here at Onward Trip are Chateau Chenonceau and Chateau de Chambord.

Chateau Chenonceau – courtesy of Air Touraine

Chateau Chenonceau is named after Chenonceaux village, the chateau’s land a mill next to Loire tributary River Cher. Chenonceau as it’s known today was designed by architect Philbert de l’Orme between 1514 and 1522 (following Thomas Bohier (King Charles VIII’s chamberlain) leveling the first structures at the property by 1513). In 1535, Chenonceau was seized from Bohier’s son and Henry II, after Francis I’s death, bestowed it to his mistress Diane de Poitiers (whose intellect and verbal skills influenced Henry II’s decisions and policies). Poitiers’ stewardship was when a bridge across the River Cher to connect Chenonceau to her home and Chenonceau’s gardens were built.

Henry II wasn’t what one would call faithful to his wife Catherine de Medici (same prominent Italian Renaissance family) due to his mistress Diane de Poitiers. Medici and Poitiers were aware of his adultery and “battled it out” so to speak even after his 1559 passing, when Medici was regent to her then child son Francis II. Catherine won out it appears. She ordered Diane to transfer Chenonceau stewardship to Catherine in order to get different Loire Valley estate Chateau de Chaumont and expelled Diane from French royal political life.

Catherine de Medici – courtesy of The Florentine

Catherine moved Francis II to Chenonceau and drew from her Italian heritage to add designs to the estate. Francis II’s practically ceremonial ascendance to the throne (he was too young to make royal decisions yet, those were made by Catherine herself being regent) was celebrated by Catherine with the first fireworks display in France. Chenonceau’s gallery across its bridge was built by then so its residents could exercise without leaving the estate’s safety.

Jean Bullant added designs and structures between 1570 and 1576.

Chateau de Chenonceau wasn’t destroyed during the French Revolution due to those who claimed it at the time describing its bridge as the only at the River Cher for miles. During World War II, the chateau was bombed, its chapel’s windows destroyed and its gardens flooded. The gallery at the bridge was where many French secretly escaped from Nazi occupied territory to free territory at the other side of the Cher.

During the 1950s, Chateau de Chenonceau was rebuilt.

Chateau de Chambord is at the Boulogne forest massif where the Counts of Blois lorded, yet by 1498 the area where the chateau is was royal domain. The territory went from Mont-près-Chambord in the west to la Ferté-Saint-Cyr in the east. Its northern boundary ran parallel the somewhat distant Cosson river, while the southern confines of the massif were close to the course of the Beuvron river.

Chateau de Chambord – courtesy of The Loire Valley

Francois I, King of France beginning in 1515, imagined a castle in a park in Boulogne forest massif on farmland north of Cosson. His reason was hunting grounds for himself and other royals (in France, England, and other areas of medieval Europe, forests, then wildlife enclosures for wealthy hunters, were despised by people who weren’t royals since they restricted lower class access to forest economics; being medieval Christian Europe, it was rare for true regard for wildlife and even domesticated animals to be acknowledged). The chateau’s construction began in 1519 simultaneously to a 6200 acre purchase of cultivated areas, groves, and heaths where peasants’ sheep food was.

Francois I – courtesy of Paris Diary by Laure

Chambord grew to 13500 acres by 1645, when Gaston Duke of Orleans finished the border. The border, dry lacustrine Beauce limestone, was opposed by residents who until then utilized the forests for poaching. Gates were closed during the evening until the 20th century, later entrances let in vehicles and kept wildlife out.

In 1542, Francois I tasked captains at Chambord with these responsibilities: maintain plants, keep hunted animal populations from waning and exploding, and check logging operations. The captains, partly by being supervised little and mostly their own terrible decisions, were known to abuse their power by being violent to many residents, some of whom weren’t ethical themselves given their breaching the chateau’s borders. The captains’ behavior was terrible to where by 1777, Louis XVI’s reign, their authority at Chambord was permanently suspended.

The chateau stood despite being looted during the French Revolution. Abandoned for years, Chambord was donated by Napoleon Bonaparte to Marshal Berthier in 1809. By 1821, Chambord was offered by a national subscription to the Duke of Bordeaux, grandson of King Charles X. His politics connected exile did not allow him to live in his castle, which he named “Count of Chambord”. He only discovered his estate in 1871 during a short stay in which he wrote “Manifesto of the White Flag”. He refused France’s tricolor flag and the throne. Despite his absence, his employees were attentive to the estate. A steward guided restoration campaigns and officially opened Chateau de Chambord to the public. In 1883, year of the duke’s death, the estate was inherited by his nephews the Princes of Bourbon-Parme.

From 1930 into today, the chateau and its national park are governed by France’s government.

The chateau wasn’t impacted by World War 1. World War 2? It wasn’t as fortunate. In 1939, following the evacuation of the main museums in Paris, thousands of works of art were sent in convoys to eleven castles and abbeys in central and western France, including Chambord. The castle, which was closed to the public, housed thousands of works of art, mostly from French public collections, in order to protect them Nazi greed and destruction. With 4,000m3 of crates stored in June 1944, Chambord was the largest of the 83 French depots housing art. Iconic works such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Delacroix’s Liberty Guiding the People and The Lady with a Unicorn were hidden in Chambord. Thanks to French efforts, art and Chambord itself survived.

References:

- “Château”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ch%C3%A2teau

- “Geology & Geography of the Loire”. Jon-David Headrick Selections. https://www.jondavidheadrick.com/geology-and-geography-of-the-loire

- “Historic Loire Valley”. Odyssey Traveller. https://www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/historic-loire-valley/

- “World War II French Resistance in the Touraine Loire Valley — La Roche Posay Hostage Crisis”. Days on the Claise. 12 May 2021. https://daysontheclaise.blogspot.com/2021/05/world-war-ii-french-resistance-in.html

- Bilder, James. “Ireland in World War II: The Swastika vs. The Shamrock”. Warfare History Network. 2018. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/ireland-in-world-war-ii-the-swastika-vs-the-shamrock/

- “Château de Chenonceau: The Château of Fairytales”. European Waterways. https://www.europeanwaterways.com/blog/chateau-de-chenonceau/

- “As History Unfolds”. Domaine National de Chambord. https://www.chambord.org/en/history/the-park-of-chambord/as-history-unfolds/

- “Visiting the château”. Domaine national de Chambord. https://www.chambord.org/en/discovering/the-castle-visit/