- Historic Hanukkah Happenings – Per Rabbis

- Historic Hanukkah Happenings – Other Perspectives

- Utilizing, and Not Utilizing, the Holiday’s Source

- Hanukkah for Those Who Don’t Celebrate It

- Traditions

- Sephardi Hanukkah vs. Ashkenazi Hanukkah

- Mizrahi Hanukkah

Hanukkah is a Jewish holiday seen as its equivalent to Christmas. It occurs on the 25th of Kislev per the Jewish calendar, during November or December per the Gregorian calendar. Anybody unfamiliar with it and its history would be bewildered to know it is a lesser holiday according to Rabbinic documents, that it doesn’t always align with Christmas’ December occurrence, and there are Jewish denominations that don’t celebrate it.

Courtesy of CultureAlly

Historic Hanukkah Happenings – Per Rabbis

Hanukkah’s historic basis occurred circa 200 B.C. Judea was reigned by Antiochus III, Seleucid king of Syria. Seleucid denotes the Greek dynasty that ruled Syria and other parts of the Middle East from 312 B.C. to 64 B.C. Antiochus III allowed Jews to remain at Judea and practice their faith. Antiochus III’s son Antiochus IV Epiphanes outlawed Judaism and forced its adherents to worship Greek gods. In 168 B.C., the Seleucid military went to Jerusalem, massacred its inhabitants, and disrespected the Second Temple and what it stood for by building an altar to Zeus and sacrificing pigs there.

Jewish priest Mattathias and his five sons sparked a rebellion against the Greek overlords. Following Mattathias’ death in 166 B.C., his son Judah Maccabee led the rebellion. Over the next two years, Jews drove out Seleucids out of Jerusalem. The Second Temple’s Jewish altar was rebuilt and the menorah (candleholder), whose seven branches represented knowledge and creation, its candles to be burned every night, was lit.

Recreation of the Maccabean Revolt – courtesy of Weapons and Warfare

According to Rabbinic documents, a miracle occurred regarding the menorah. There was only enough olive oil for the candles to burn a single day, yet the flames kept going for eight nights. Hanukkah was non-existent for centuries since its events were after those of the Hebrew Bible. After the miracle of the olive oil’s burning, Jewish sages were inspired to create a festival honoring it.

Historic Hanukkah Happenings – Other Perspectives

There are interpretations of the Maccabean Revolt differing from Rabbinic declaration. The first Book of Maccabees describes an eight day celebration following the Second Temple’s refurbishment, making no reference to the lighting miracle. There are modern historians who offer a different version of the revolt’s events. They claim Antiochus IV-led Jerusalem was a city of civil war between Jews who adapted to the rulers’ Greek and Syrian culture and Jews who sought to impose Jewish laws and traditions. Traditionalists won, the Hasmonean dynasty (governed by Judah Maccabee’s brother and descendants) reigning Israel following the Greek and Syrian eviction, maintaining a century-lasting independent Jewish monarchy.

Jewish scholars hint the first Hanukkah was a belated Sukkot celebration. Sukkot is a Jewish autumn festival beginning the 15th day of Tishri (Gregorian calendar’s September or October), five days after Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). Sukkot is a Pilgrim Festival of the Hebrew Bible, honoring when the Israelites lived in huts (sukkot) when they wandered the wilderness after their Exodus from Egypt. The Maccabean Revolt’s turmoil would temporarily end the safety of Sukkot celebrations, necessitating their occurrence later.

Sukkot booth – courtesy of The Spruce Eats

Utilizing, and Not Utilizing, the Holiday’s Source

The Biblical Archaeology Society’s Jonathan Klawans explains, “there’s … something peculiar about Hanukkah … Passover, in commemoration of the Exodus from Egypt, the home ritual is based on the Passover Haggadah, which retells the story of the Israelites’ liberation from slavery … Purim, commemorating Queen Esther’s thwarting … an evil plot against the Jews of Persia, Jews gather in synagogues and … read the biblical Book of Esther … commemorate the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, the … Book of Lamentations is … intoned. Yet when … Hanukkah lights are lit, there is no formal telling of the story. A few prayers … relay the story … in simple, abstract generalizations”.

Hanukkah isn’t in the Hebrew Bible, and the Talmud’s retelling misses details like who Antiochus and the Maccabees were. The entire story is within 1 and 2 Maccabees, neither Rabbinically canon.

Unlike 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, and 1 and 2 Chronicles, 1 and 2 Maccabees are independent, though similar, books telling the same story (somewhat like establishing the story of Jesus using the Gospels of Mark and John). 1 Maccabees was a Hebrew work from the land of Israel. 2 Maccabees was a Greek language work from Jewish diaspora.

A passage goes: “They celebrated it for eight days with rejoicing, in the manner of the festival of booths [Sukkot], remembering how not long before, during the festival of booths, they had been wandering in the mountains and caves like wild animals. Therefore, carrying ivy-wreathed wands and beautiful branches and also fronds of palm, they offered hymns of thanksgiving to him who had given success to the purifying of his own holy place. They decreed by public edict, ratified by vote, that the whole nation of the Jews should observe these days every year (2 Maccabess 10:6-8)”.

Again, it lends credence to the theory Hanukkah began as a delayed autumn harvest festival. Klawans elaborates, “This makes … sense, especially when we recall … Solomon’s temple was dedicated on Sukkot (1 Kings 8:1–2). Traditionally-informed Jewish readers may know of other ways … Hanukkah recalls Sukkot, including … recitation of the unabbreviated Hallel (Psalms 113–118), read in entirety on Sukkot and Hanukkah … These … may be telling, but we must turn to 2 Maccabees 10 for the surest confirmation of this sound explanation for the eight-day … Festival of Lights”.

Benno Elkan’s Knesset Menorah tribute to the Maccabean Revolt, Israel – courtesy of Museum of the Bible

Maccabees 1 and 2 would be solid scriptural support for Hanukkah, but most Jews see them as Apocrypha, psueudo, quasi or anti canon, similarly to Christians’ views of that faith’s Apocrypha.

Traditional Jewish retellings of the Hanukkah miracle leave out Maccabees’ rise was in response to Jewish efforts to accommodate Greek rule by challenging traditional Jewish practices. More tellingly, ” 1 and 2 Maccabees agree on one fundamental point … glossed over or not mentioned at all in [many] retellings of the Hanukkah story: The Maccabees fought not only against foreign oppressors … but … Jewish assimilationists … aligned with Antiochus … the Maccabean revolt was … a civil war”.

It explains why Jews tend to avoid the Maccabees books, even as they form the basis for Hanukkah: “How can one celebrate a one-sided victory … Would the defeated or their descendants want to celebrate their loss? In the effort of encouraging all Jews … to celebrate the new festival … the civil war goes unmentioned; the holiday celebrates … the defeat of the foreign enemies”. Working against Maccabees’ inclusion were the books and holiday were, at the time, recent, and 2 Maccabees was discarded for being Greek instead of Hebrew.

Klawans goes again: “While excluded … by Jews, these books … were preserved … by Christians … For early Christians, Greek was no object: The Gospels were in Greek … For early Christians, recent writings were no object: All the writings of the New Testament were relatively recent … for early Christians centuries ago [and] today, the stories of the Maccabean martyrs are seen as important precedents for Jesus and other early Christian heroes who chose … death over military resistance. Each of these books holds interest for Christians … each holds interest for Jewish readers”.

Hanukkah for Those Who Don’t Celebrate It

Karaite Jews don’t celebrate Hanukkah given it isn’t described by the Hebrew Bible. A Blue Thread, a Karaite blog, says, “Hanukkah commemorates one of the most successful rebellions in the history of our people. The Maccabees, as they are commonly referred to, were the heroes and leaders of a rebellion against the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. Because of the Maccabean Revolt, the Jewish people reclaimed The Temple and rededicated it to the God of Israel. The word Hanukkah is Hebrew for “dedication””.

Karaite worship – courtesy of The Jewish Standard

ABT elaborates, “The Maccabees … the Hasmoneans … were closely aligned with the Sadducees … a Second Temple Jewish movement that, like Karaites, opposed the concept of an oral law”. Karaites aren’t directly connected to the Sadducees, though there are Karaites who see their movement as heirs.

The strongest opponents of the Sadducees were the Pharisees, theological ancestors of Rabbinic Judaism. ABT continues, “Rabbinic Judaism is the normative form of Judaism … all others are compared [to]. Against the Rabbinic backdrop, it is easy to call Karaites “rebellious.” This is particularly so if one’s view is that Karaites stripped the Talmud away from their Jewish canon … Karaites and other historically Tanakh only movements … never [accepted] the Talmud in the first place“. A Karaite celebration of Hanukkah would be submission to the movement whose [indirect] theological ancestors opposed theirs.

Plus, “Hanukkah, at its heart, celebrates the rededication of the Temple; but today the Temple is not standing. So [from Karaites’ perspective] a celebration of Hanukkah” isn’t appropriate.

Another Hanukkah-averting denomination, at least historically, are Ethiopian Jews. Ethiopian Jews lost connection to Jewish communities globally before the Second Temple was destroyed, so they were unaware of the oral Torah (whether they would adopt it or resist it like the Karaites is speculative). Ethiopian Jews were unaware of Hanukkah and other Rabbinic traditions, due to managing their lives according to the written Torah.

Former Ethiopian Jewish worship house – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Traditions

Lighting the Hanukkah menorah is a tradition going back 1,800 years. Earlier lightings were only a single candle to mark the rededication of the Temple before moving to eight candles. Ever since, nine-branch menorahs are standard, eight of the candles lit by the ninth.

Courtesy of HISTORY

Displaying the menorah during Hanukkah is another tradition, announcing to the world the miracle at the holiday’s heart. Menorah lighting ceremonies at times occur at the same time as Christmas tree lightings.

Courtesy of Goldsteins Funeral

Dreidels are yet another tradition. Its origins aren’t clear, their first appearance in 18th century Jewish writings. It’s believed these tops were adaptations of German Christian traditions. German dreidels were labelled with a letter on each side, notifying whether the person who spun the top should take all, none, or in between of coins in a pot or offer their own. Yiddish, closely related to German, replicated the Christian edition of the game. Each Hebrew alphabet character on Jewish dreidels is the first letters of “nes gadol haya sham”, or “a great miracle happened there”.

Courtesy of The MIT Press Reader

Gelt, from Yiddish for “money”, is a Hanukkah tradition that didn’t originate among Ashkenazi Jews. It was first known during the 16th century, among Mediterranean Jews. Among them, money was collected to buy or make attire for the poor. By the 19th century, Eastern European Jews offered coins as Hanukkah gifts in what was likely an interpretation of the Mediterranean tradition. By the 1920s, U.S.-based businesses, like Loft’s Candies, made chocolate Hanukkah gelt wrapped in gold foil. The tradition continues among many Jews.

Courtesy of NPR

Songs exist for Hanukkah as they exist for Christmas. They range from Maoz Tzur, a song of praise, to more casual celebrations of the holiday.

To commemorate the oil, fried foods are eaten.

Latkes at center – courtesy of Food Network

The Jewish alternate to Christmas wouldn’t be so without presents – and, astoundingly, it wasn’t always a tradition. Present giving was traditionally a Purim event, a Spring event no less, until the 1880s, when American Jews adapted Christmas traditions. By the 20th century, the Yiddish press ran articles and ads encouraging Jewish immigrants to buy Hanukkah presents. Post-World War II commercialism led to a boom for Christmas and Hanukkah presents. There are Jewish families who give a present each on each of the eight nights.

Lastly, dairy eating is a Hanukkah tradition. As with the presents, the practice was prior a staple of a different holiday, Shavuot, a late spring or early summer festival. Hanukkah dairy is getting attention for its tribute to Judith, who led General Holofernes to his death with dairy, saving the Jewish nation.

Sephardi Hanukkah vs. Ashkenazi Hanukkah

Differences between Sephardi (Spanish rite) and Ashkenazi (German rite) Hanukkah celebration are mild, says Halakha of the Day’s Yosef Bitton.

He elaborates, “According to … Ashkenazi custom, the auxiliary candle or shamash is lit first … after saying the berakha one lights the rest of the candles with the Shamash … The Sephardic tradition … is [lighting] all the candles with a match or a separate candle … only at the end is the shamash lit. Whereas for the Ashkenazi tradition, the shamash is also used to light the candles, in the Sephardic tradition, it is not; since the main reason the shamash is lit is to avoid a benefit from the light of the Hanukka candles, in case we involuntarily use the lights of those candles”.

He continues, “Many Sephardic families, especially in Israel, keep the original custom of lighting the candles outside the house, on the opposite side of the Mezuza … The Ashkenazi tradition … [lights] the Hanukiah [menorah] inside the house, near a window, so … it can be seen from the outside”.

Moving on, “In many Ashkenazi communities, the custom is that each family-member lights their own Hanukiah … In Sephardic families … it is customary to light only one Hanukia per family. This is similar to the case of Shabbat candles: whereas according to the Sephardic tradition, only the mother lights the Shabbat candles; according to the Ashkenazi tradition, each of the daughters in the family lights their own Shabbat candles”.

Lastly, “According to the Ashkenazi tradition in the Berakha, one says: “lehadliq ner SHEL Hanukka”, (… to light the Hanukka candle). While Sefaradim says, following the words of the Shulhan ‘arukh: “lehadliq ner Hanukka”, omitting the word “SHEL”. There is no grammatical or semantic difference between these two versions. And one can not say that one version is correct and the other is not. Actually, the original version of this berakha (Maimonides, MT Hanukkah 3: 4) is “lehadliq ner SHEL Hanukka”, similar to “lehadliq ner SHEL Shabbat”. The Sephardic tradition, which generally follows Maimonides, is based, in this case, on the opinion of the Mequbalim. Some Sefaradim, however … retained the original version of Maimonides which includes the word “shell”, and so was the tradition in Iran”.

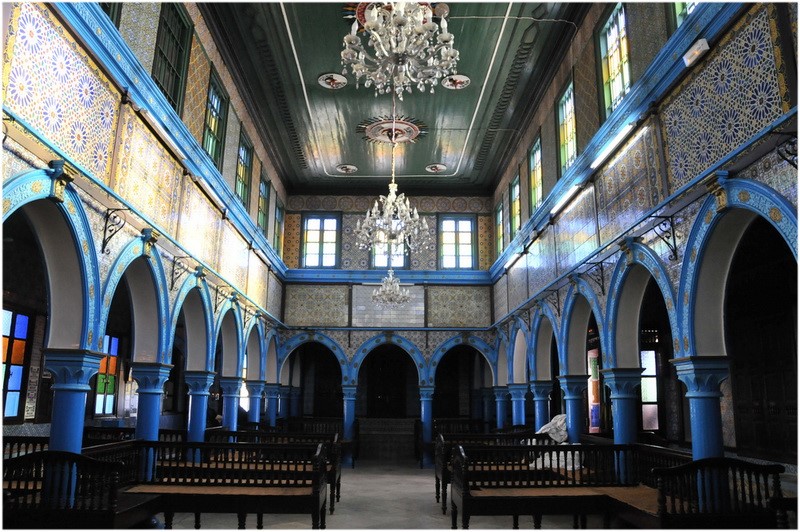

Mizrahi Hanukkah

Tabby Refael of the Jewish Journal describes Hanukkah for Jews of Iranian descent such as herself: “in Iran, a Shiite country, the lure of Christmas didn’t exist … rendering the Americanized eight nights of Hanukkah gift-giving nonexistent. In Iran, we … kept our glowing hanukkiahs as far away as possible from windows and anywhere else that would [say], “A Jewish family lives here.””. Consequently, Iranian Jews aren’t afforded many unique Hanukkah traditions.

Synagogue in Isfahan, Iran – courtesy of Pars Today

Mizrahi Jews, though, are.

Refael says, “In Yemen and North Africa, the seventh night of Hanukkah marks Chag Ha’Banot (“Eid Al Banat” in Judeo-Arabic), or The Festival of Daughters … The festival, which usually falls on Rosh Chodesh Tevet, involves singing, dancing and lighting the hanukkiah in honor of Jewish women like Judith, the young widow-turned-heroine of the Hanukkah story who fought against assimilation (the Book of Judith is on par with the Book of Maccabees itself)”.

Proceeding, “In countries like Libya and Tunisia, women traditionally went to synagogue on Chag Ha’Banot to touch the Torah and pray for their daughters’ health; young women and old women would dance together; girls who had turned their backs against one another would reconcile; and, in many communities, there was a dairy feast in honor of Judith, who falsely told the Syrian Greek General Holofernes she’d help him and his army take the city of Bethulia, offering him salty cheese and wine and then, once he was drunk enough, beheading him. The sight of their headless general terrified enemy soldiers into fleeing and revived the morale of Maccabee fighters”.

El Ghriba synagogue, Tunisia – courtesy of Breaking Matzo

Moving along, “While Moroccan Jews prefer wicks dipped in olive oil, Jews in India use coconut oil to light their hanukkiahs and enjoy … Indian treats, such as deep-fried onion pakoras and gulab jamun, fried balls of dough dipped in syrup. Moroccan Jews enjoy sfenj, deep-fried donuts with orange zest (often on the third night of Hanukkah)”.

Moroccan synagogue – courtesy of The Forward

Indian synagogue – courtesy of Rethinking The Future

Continuing, “For some communities, safety and protection were important themes during Hanukkah. Many Syrian Jews from Aleppo … trace their Sephardic ancestry to … Jews expelled from Spain in 1492”. A special custom among them is lighting an extra flame each night of the holiday. It “represents their gratitude for the safety and tolerance they encountered in their adopted homeland of Syria. According to one interpretation, they arrived in safety in Syria after the expulsion on the first night of Hanukkah, and they viewed their arrival in safety as their own miracle of Hanukkah”.

References:

- “Hanukkah”. History. 27 October 2009 (Publication), 27 November 2023 (Revision). https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/hanukkah

- “Seleucid”. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Seleucid

- “Sukkot”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sukkoth-Judaism

- Berthelot, Katell. “The Maccabean Victory Explained: Between 1 and 2 Maccabees”. The Torah. https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-maccabean-victory-explained-between-1-and-2-maccabees

- “Rejection, Rebellion, and Revolt”. A Blue Thread. 4 December 2012. https://abluethread.com/2012/12/04/rejection-rebellion-and-revolt/

- “Why Rabbi Rosen at the algemeiner is (Mostly) Wrong about Karaite, Persian and Reform Jews”. A Blue Thread. 21 October 2014. https://abluethread.com/2014/10/21/rabbi-rosen-algemeiner-mostly-wrong-karaite-persian-reform-jews/

- Yuko, Elizabeth. “8 Hanukkah Traditions and Their Origins”. History. 21 December 2022 (Publication), 28 November 2023 (Revision). https://www.history.com/news/hanukkah-traditions-origins

- “10 Things You Didn’t Know About Ethiopian Jews – Especially for the Sigd Holiday”. The Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore. https://associated.org/stories/jewish-ethiopian-traditions/

- Bitton, Yosef. “Sephardic vs. Ashkenazi traditions in Hanukkah”. Halakha of the Day. 14 December 2022. https://halakhaoftheday.org/2022/12/14/bourekas-or-latkes-sephardic-vs-ashkenazi-traditions-in-hanukka/

- Refael, Tabby. “Beyond Gelt: How Mizrahi Jews Celebrate Hanukkah”. Jewish Journal. 16 December 2020. https://jewishjournal.com/commentary/columnist/326126/beyond-gelt-how-mizrahi-jews-celebrate-hanukkah/

- Klawans, Jonathan. “Hanukkah, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and the Apocrypha”. Biblical Archaeology Society. 3 December 2023. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/hanukah-maccabees-and-apocrypha/