- Grim (To Bittersweet) Early Lives

- Grimms and Germany

- Some More Info About the Stories

- Societal Context for the Scariness

- Among the Grimmest Parts of the Grimms’ Works

- Legacy of the Grimms

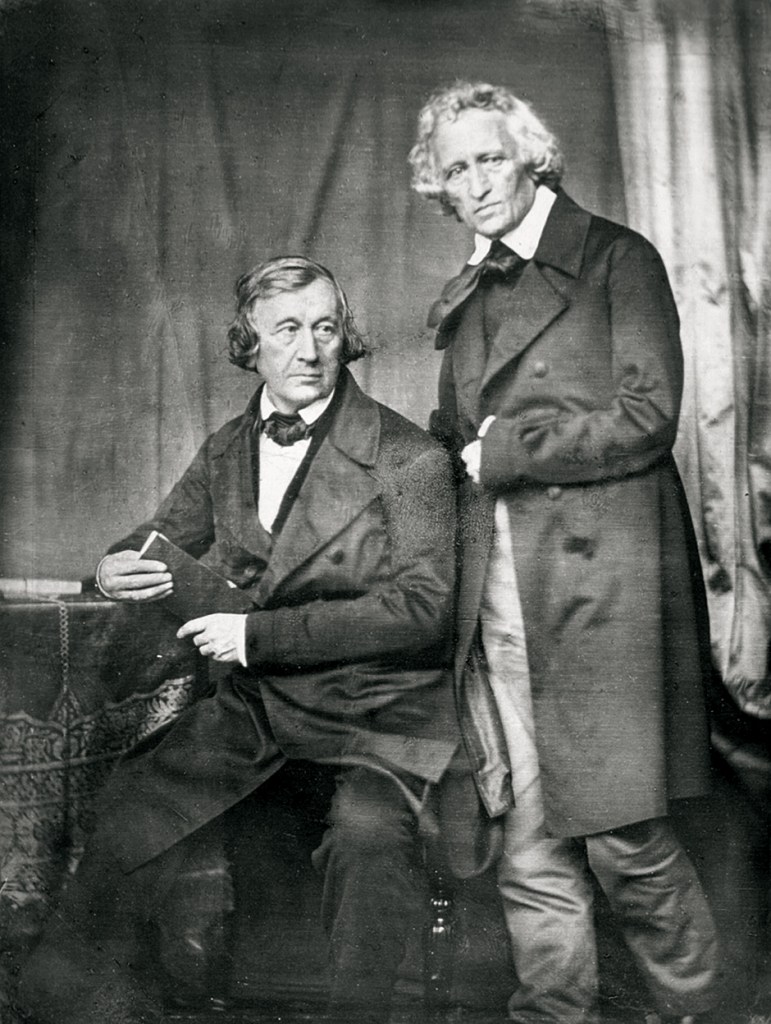

Jacob (right) and Wilhelm (left) Grimm, 1847 – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Grim (To Bittersweet) Early Lives

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was born January 4, 1785 in Hanau, Hesse-Kassel. Wilhelm Carl Grimm was born February 24, 1786 in Hanau, Hesse-Kassel. Phillip Wilhelm Grimm, their father, was Hanau’s town clerk and later held a position in Steinau. In 1796, Phillip Wilhelm passed away.

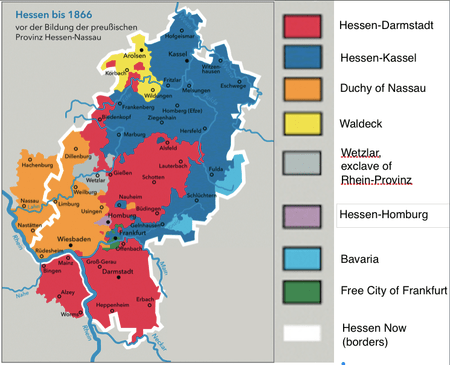

Hesse modern borders and borders circa 1866; many other German lands were as scrambled as this until Prussia maneuvered them into unity, minus the Hapsburg-ruled Austria; note Bavarian territory; Bavaria to this day isn’t that tiny, it’s that these were pockets owned by the kingdom; other German principalities were core zones and their far-afield enclaves – courtesy of FamilySearch

Hanau, Hesse – courtesy of FrankfurtRheinMain

Phillip Wilhelm’s death left the Grimms to financial struggle. The family’s grandfather supported them, but two years later he too died. Jacob and Wilhelm’s mother, Dorothea Grimm, died in 1808, meaning the brothers, more so the elder Jacob, were the caretakers of their brothers and sister.

Ken Mondschein, PhD, of Hadley, Massachusetts elaborates on the Grimm Brothers’ circumstances in “Introduction”, a section of “Grimm’s Complete Fairy Tales” (an edition – translated by Margaret Hunt – of the tales as originally published). Owing to being pushed off the cliff of middle class life into poverty, the Brothers Grimm’s “first priority was always to study hard so that when they grew up, they could provide for their family and re-create the comfortable home life”.

Mondschein supplements, “The loss of their father and their descent into poverty also marked their personalities: Jacob was serious and strong; Wilhelm was more outgoing, but physically frail. Their unfortunate circumstances are evident in their work: the Grimms favored stories with an absent father and a younger sister to be protected”.

At the same time, Mondschein elaborates, “Their fortunes were not entirely bad … Thanks to Henriette Zimmer, a maternal aunt and their “fairy godmother”, the brothers were educated at Lyzeum … in Kassel”.

Later, the brothers were advised to enroll at the University of Marburg. However, Jacob, the first to apply, “was turned down when he first applied … because he didn’t belong to the right level of society. The university was in the kingdom of Hesse … the rulers … decreed that since there were too many students applying … only those in the legally defined top seven levels of society could attend. Jacob Grimm, as the son of a magistrate, fell into the eighth level of society so the university refused to accept him no matter how good a student he was”.

Someone wrote a letter to Hesse’s ruler requesting special permission for Jacob to attend, which was granted. Wilhelm in time accompanied Jacob at Marburg.

It was at Marburg where they studied German folklore and customs in earnest.

Kassel, Germany – courtesy of TripSavvy

Grimms and Germany

Marburg, Germany – courtesy of Nomads Travel Guide

A favorite professor of the brothers at Marburg was Friedrich Karl von Savigny. He, “didn’t give dry lectures and expect the students to copy down and memorize lists of facts. He encouraged them to expand their thinking and gave … access to his library. In those days, free public libraries were not an option so access to these books opened up new worlds for the Grimms”.

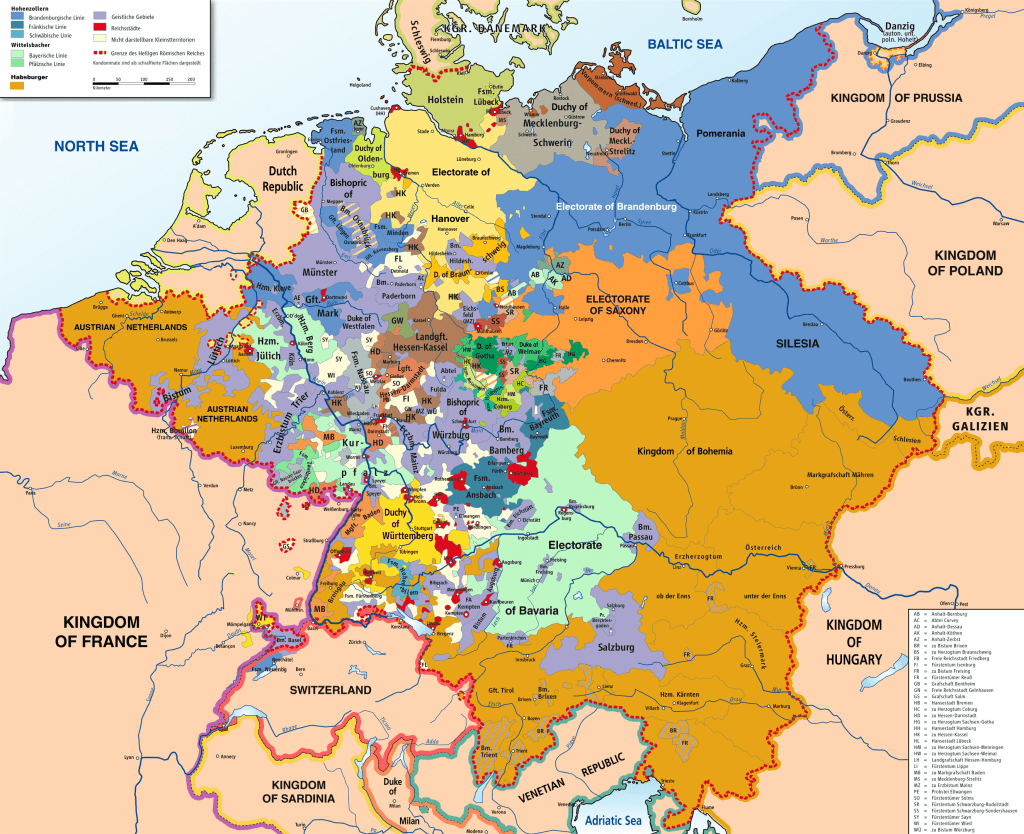

Savigny and others “taught them that to really create a new Germany – a Germany of laws that was more legitimate than the mishmash of the Holy Roman Empire – they … tap the … well of folk custom and belief … collecting notebooks of Märchen [folk tales and fairy tales]”.

Holy Roman Empire by the 1800s, near its end; Hesse-Kassel, home of the Brothers Grimm, is the brown-shaded territory in the center – courtesy of Unofficial Royalty

LibraryPoint says, “The Grimms gathered stories – and not just from their library books. They also went out and found storytellers who remembered … tales. These people might be housewives … craftsmen, or servants. They asked their friends for help, too”.

Mondschein says fairy tales were heard and collected before, i.e. Aesop’s Fables, but until the Grimms arrived these were written “to impress an audience of sophisticated adults”. The Grimms and some in the field after tried to “set such stories down in their supposedly “pure” form, given no false shine by literary varnish; to subject them to “scientific” study”, and invoke that these were for a wider audience.

Besides personal interest, the Grimms’ methods were for political reasons too. Germany as it exists in the present didn’t exist then – it was a mishmash of emerging, expanding, shrinking, and disappearing feudal states – but adherents of the then-burgeoning German nationalist movements wished for it. Instead of being peoples such as Prussians and Hessians and Bavarians, the Grimms and their contemporaries “wished to be citizens of a new, democratic nation that would unite all the German-speaking lands in peace and prosperity”.

The Grimms presented the stories they recounted, from many German lands, as representative of a supposed “national character”, even though there were established regional identities. Even so, their work was critical to many German lands later uniting, if divided by the Prussian north and central and the Hapsburg southeast (Austria). Alsace was contested for years until it landed in permanent French grip after World War II. Switzerland, owing to its political organization and solid national mentality among its citizens, was majority-German-speaking but opted out of unification with other German lands. Liechtenstein was of little interest for being so little; Paul Barbato, host of YouTube series Geography Now, in the episode on Liechtenstein references the micronation was so geographically insignificant, not even the National Socialists wished to annex it.

Dialect continuums in Germany; the variety and their regional associations (never mind the political territories’ changing) already subverted the ambitions of a German “national character” ideology promoted by the Grimms and contemporaries; the history of the region (plus Alsace, Switzerland, Austria, and Liechtenstein) was for the most part disunity among its peoples – courtesy of SpringerLink

The folktales the Grimms and their contemporaries gathered were important to Germans for another reason. At the time, many German lands were seized or threatened with seizure by the Napoleon-led French, so Germans “were … interested in preserving their history and their ways of life”.

Napoleonic forces in German territory, per François Gérard’s 1810 painting “Battle of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805” – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Some More Info About the Stories

Jack Zipes, of the National Endowment for the Humanities, says, “They [meant] to trace and grasp the essence of cultural evolution and … [showcase] how natural language, stemming from the needs, customs, and rituals of the common people, created authentic bonds and … [created] civilized communities”.

Similar in cultural goals to the fairy tales was the Grimms’ “Deutsche Wörterbuch”, a study of High German and its incarnations’ history; just as important as their fairy tales but, as Mondschein points out, an endeavor whose laudability is overlooked today; it wasn’t finished until the 1960s, by scholars who continued the brothers’ work after their deaths – courtesy of Deutscher Apotheker Verlag

The first edition, opposite the final edition, is rife with short, sparse features. Zipes quotes from each edition of “Rapunzel” to prove his point:

Edition #1: “Once upon a time there lived a husband and wife who had been wishing for a child for many years, but it had all been in vain. Finally, the woman became pregnant. Now, in the back of their house the couple had a small window that overlooked a fairy’s garden filled with all kinds of flowers and herbs. But nobody ever dared to enter it”.

Edition #7: “Once upon a time there was a husband and wife who for quite some time had been wishing in vain for a child. Finally, the dear Lord gave the wife a sign of hope that their wish would be fulfilled. Now, in the back of their house the couple had a small window that overlooked a splendid garden filled with the most beautiful flowers and herbs. The garden, however, was surrounded by a high wall, and nobody dared enter it because it belonged to a sorceress, who was very powerful and feared by all”.

The Christian motif implementation is interesting, for, per Mondschein, a goal of the Grimms was assembly of stories with storytelling ancestry from a pre-Abrahamic world – hence, “once upon a time”. Since Germanic mythology creatures such as trolls and dwarves are, classically, incongruous with Abrahamic cosmology, they regularly take the place a human would (similar to talking trees and the like).

The first edition was a conglomerate of works from “diverse storytellers who believed in the magic, superstitions, and miraculous transformations of the tales. It may be difficult for us to understand why this is the case, but for the storytellers and writers of these tales, the stories contained truths about the living conditions of their times”. These weren’t from peasants, but literate individuals, who, after hearing the stories from illiterate or nameless informants, passed them to the Grimms.

The Grimms’ tales resonate with global audiences, even as early as the first edition, for they nudge readers to transform themselves and their conditions to make the world a better place.

Societal Context for the Scariness

Mondschein notes that the original edition of the Grimms’ tales is terrifying by modern standards. Many characters “get hurt or disfigured … die by disease, accident, or violence”. In the Grimms’ first edition of their “Cinderella” take, “Cinderella’s wicked stepsisters … cut off parts of their feet, their eyes … pecked out by birds”. Disney “omitted Snow White’s wicked stepmother’s cannibalistic tendencies and how she was, at the end of the Grimms’ version, made to dance in shoes filled with hot coals until she fell down dead”.

He explains, “Many of the themes in fairy tales [including the Grimms’] are based on the realities of living in a world before modern medicine or agriculture, and where being “poor” meant more than … limited access to fresh produce – it meant not eating at all”. What’s more, “To lead … into the forest to die [referring to Hansel and Gretel] because there’s not enough to eat seems unthinkable to us in an age where supermarkets are filled with food … However, in a society with no strong central government [as in German lands], this was a scarily believable situation”. Mondschein tops this section with, “It’s no wonder that food and middle-class home comforts feature so heavily in many of the Grimms’ tales”.

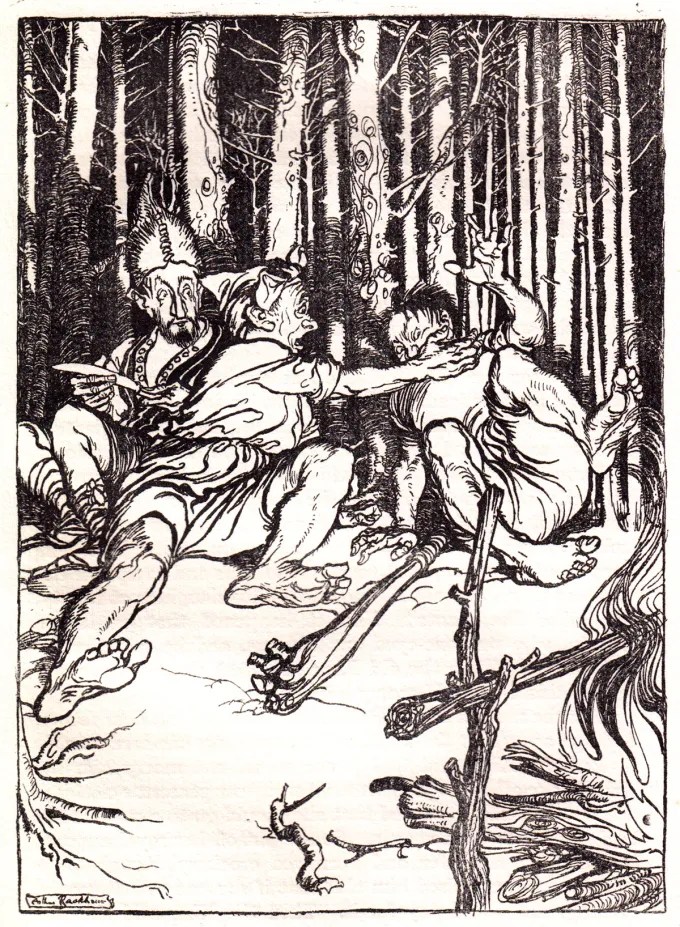

As for the home, he says it was “a place of safety and light, while the night outside was dark and scary. In the Grimms’ time, there were no flashlights, or even streetlights”. As opposed to many other European countries at the time, many of the Germanies were densely forested (1/3 of the land area today is); even the Ancient Romans were in awe at the region’s forests, though their tendency to exaggerate and fabricate about their enemies and enemies’ territories leaves room to interpretation and critique. Though the woods even now are regarded as woven into German cultures (northern Germany a reoccurring outlier), when the Grimms lived it was also “a place of fear and peril”.

Courtesy of Northlandscapes

Arthur Rackham illustrational accompaniment to a Brothers Grimm fairy tales edition; deliberate or not, Rackham conveys the fascination with and apprehension to forests in German lands – courtesy of The Marginalian

Natural dangers were one hazard, “Robbers were another: law enforcement was minimal, and penalties for even small infractions” were harsh, “So … criminals who escaped local authorities often made new lives in the forests, attacking unguarded travelers. Thus, the boundary between home and the outside, of order and disorder, was … important”.

In the United States of America and places that take after it, looking out for oneself is almost a virtue. As Mondschein points out: “in an agrarian society, where everyone in the village … help[ed] others with plowing, planting, and harvesting, selfishness wasn’t just rude – it could destroy a community’s order. Thus, the moral of many of the Grimms’ stories is to share one’s wealth, and not to be greedy”.

Among the Grimmest Parts of the Grimms’ Works

Quoth Mondschein: “The anti-Semitism of “The Jew Among Thorns” or “The Good Bargain” … is hard for modern audiences to stomach. However … we must see these stories in their historical context”.

Jews of the European Middle Ages were forbidden by the Church and by local authorities from practicing respectable trades and forced into doing roles, especially money lending, perceived as too distasteful or forbidden for Christians. Royalty were in need of loans on occasion, but more often it was the impoverished. A “poor widow … might pawn the family’s … possessions to a Jewish moneylender for enough … to buy food for a little while. As a result, the Jews of Europe were forced to live off of other people’s misery, which earned them no small amount of resentment”.

Mondschein elaborates that Jews, possibly more so in German lands than elsewhere in Europe, were “a convenient “other””. Royals and the Church got a “pass” when commoners’ wrath was at their door since the former framed Jews as the “root” of their woe … even though the same Royals and Church were responsible for the trouble in the first place.

Kerice Doten-Snitker, of the University of Washington’s Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, weighs in on the not-quite-unique, but certainly-stands-out violent anti-Semitism of German lands. She explains, “Jews migrated into German lands slowly in the ninth and twelfth centuries … they settled in … centers of religious and economic activity as well as some of the most established cities of the time”.

Doten-Snitker supplements, “From the end of the fourteenth century on, urban life in German lands became more precarious for Jews. The threat of violence had been constant for Ashkenazi [Central and Eastern European rite] Jews in the Middle Ages. Urban Ashkenazi communities faced violence from brigades on their way to join the Crusades, local mobs, and roving mercenary groups”.

The fourteenth century, not coincidentally, was when German cities began, by government edicts, expulsions of Jews who lived there. Territorialization and Christian religious reform amplified German expulsions of Jews by the fifteenth century.

Courtesy of University of Washington – Stroum Center for Jewish Studies

Doten-Snitker says, “Territorialization was the transitional process of political authorities attempting to establish sole dominion over specific territories; prior medieval forms of government were overlapping and did not have strict borders. At the same time, new and more prescriptive theocratic understandings of Christian piety revolutionized the relationship between rulers and their subjects by placing responsibility for community righteousness in the hands of rulers”.

1483 art, by Johann von Armsheim, of a theological debate between Christian and Jewish scholars – courtesy of The Librarians

These developments meant authorities battled for rights to resources and whose authority mattered. Governance and control of Jewish residency and activities were seen as no different conflict-wise from exercising authority, privilege bestowal, and definitions of community membership. In a Cologne instance, “it was a case where the issue at hand was not any activities or beliefs held by the city’s Jews … the … instigator of the expulsion … did not mind that Jews lived under his dominion; he just wanted them under his sole dominion”.

Mondschein adds, “This anti-Semitism, which culminated in the tragedy of the Holocaust, was as much a part of the Grimms’ world as … dire poverty [among other ills]. Thankfully, there are not many tales of this sort [across the Grimms’ Fairy Tales repertoire]”.

Mondschein, while on the topic, states that the Grimms’ original intentions, collection of authentic German literature, is to be separated from “the misuse to which nineteenth-century ideas of race and nation were put in the twentieth century”. Poignantly, “Although there is a clear line of thought that connects the ideas of “the spirit of the people” [“volksgeist” in German], which was fashionable in the Grimms’ day, and the mad ideologies of Adolf Hitler, the two are not the same thing. Furthermore, no sensible scholar today believes there is such a thing as a “spirit of the people” that manifests itself in history and culture”.

Legacy of the Grimms

Mondschein, on the topic of the lightening of the Grimms’ works in later adaptations, concludes, “the Grimms were victims of their own success”. He continues, “As the nineteenth century went on, the middle class grew in power and influence and [remade] society in its own image. Eventually, the liberal ideas of equal rights and equal opportunity for everyone won out. Whether you were Jewish or Christian wasn’t as important as how good a citizen you were”. Tragic, then, that German Jews’ fortunes turned around so quickly by the twentieth.

Added to this, “As the Industrial Revolution progressed, there was more material wealth to go around”, and people provided their families more comfortable lives. In a way, this was “an invention of the world of middle-class prosperity and home comforts that the Grimms so wanted to create. And ironically, within that comfortable environment, the brothers’ tales were judged as too harsh for the sort of world they helped build”.

Jack Zipes explains, “Between 1812 and 1857, seven editions of their tales appeared, each one different from the last, until the final, best-known version barely resembled the first”.

Continuing, the “stories in the first edition are closer to the oral tradition than the tales of the final, which [is] more … a literary collection, because Wilhelm, the younger brother, continually honed the tales so that they … resonat[ed] with a … literary public. Their books [eventually were] second in popularity only to the Bible in German-speaking lands. By the twentieth century, they [were] the most famous collection of folk and fairy tales in the western world”.

Mondschein praises their work as part of the “world canon”.

The personal opinion of the author of this post? The Grimms’ contribution to the world isn’t negligible, but the less savory qualities of their work means readers must go to their stories knowing there’s a cultural shock.

Courtesy of Condé Nast Traveler

References:

- Denecke, Ludwig. “Brothers Grimm”. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2 August 2024 (Updated). https://www.britannica.com/biography/Brothers-Grimm

- Grimm, Jacob Ludwig Carl (Author); Grimm, Wilhelm Carl (Author); Hunt, Margaret (Translator); and Mondschein, Ken, PhD (Introducer). “Grimm’s Complete Fairy Tales”. Canterbury Classics. San Diego, CA. 2011. P. xvi-xxii (Introduction).

- Virginia. “Brothers Grimm: Best Friends on the Fairy Tale Road”. Librarypoint. 21 August 2018. https://www.librarypoint.org/blogs/post/brothers-grimm/

- Doten-Snitker, Kerice. “How anti-Semitism was used to gain political power in medieval Germany”. University of Washington – Stroum Center For Jewish Studies. 26 February 2019. https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/jewish-history-and-thought/anti-semitism-medieval-germany-ashkenaz-political-power/

- Zipes, Jack. “How the Grimm Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale”. Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities. March/April 2015, Volume 36, Number 2. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/marchapril/feature/how-the-grimm-brothers-saved-the-fairy-tale