- Alemannic’s Not So Ancient Origins

- Alemannic Classification

- Alemannic isn’t all there is to German dialects

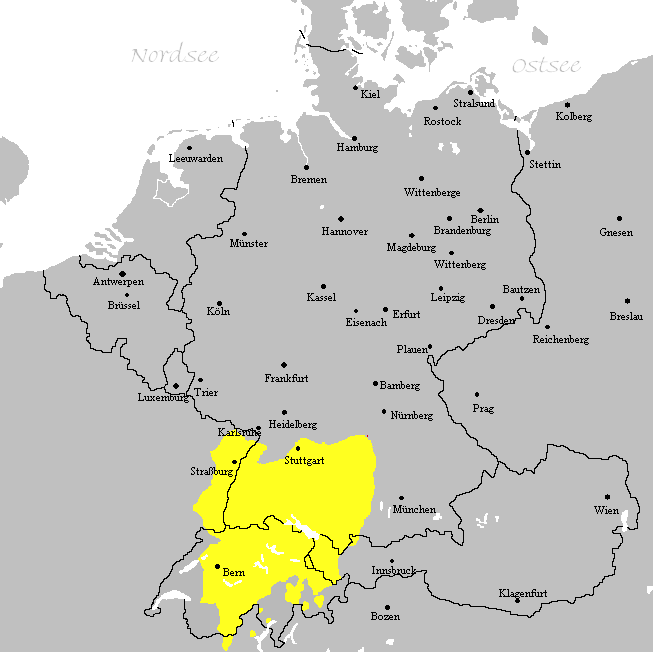

In our 2024 trip to Europe, we visited Germany’s Schwarzwald (Black Forest), and Switzerland’s Lauterbrunnen and Zermatt. Each of these locals’ speech is Alemannic.

Alemannic dialect locations (yellow); Strassburg is in France’s Alsace region (historically Alsace-Lorraine, more recently Grand Est); Stuttgart is in Germany’s Baden-Wurttemberg state; Bern is in Switzerland’s Bern canton; Liechtenstein is the tiny nation sandwiched between Switzerland and Austria; Austria’s Alemannic dialect area is its western state of Vorarlberg – courtesy of Wikidata

Alemannic’s Not So Ancient Origins

Alemannic dialects’ name is taken from the Alemanni, a tribal alliance that butted heads with the Romans. The Alemannic dialects were named after the alliance, which, if we go by historic record, is relatively recent, first appearing in 213 A.D. at the earliest. It’s possible the alliance was in existence earlier, but there’s yet to be conclusive evidence found for a “real” earliest known assembly.

Alemanni (gray) and other peoples on the fringes of the Roman Empire (purple) – courtesy of Omniatlas

The Alemanni were tied to the Suebi, who gave their name to Swabia (which, ironically, is dialectically Alemannic today). During campaigns, the tribes of the Alemanni put their militaries under joint command of two leaders. Otherwise, being linguistically-related but culturally-distinct, the peoples seldom agreed or connected with each other on anything, a central government nonexistent in the confederation.

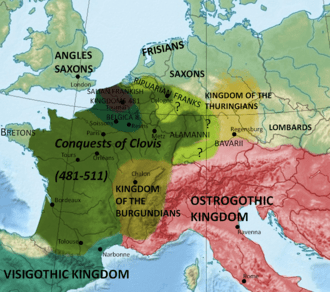

The Alemanni spread south and west in the 5th century A.D., into what are now northern Switzerland and France’s Alsace region (which retains a cultural mix best described as Franco-German). By 496 A.D., the Alemanni were conquered by and assimilated into the dominions of Clovis. Clovis, it must be stated, is regarded as one of the first “true” kings of what is now France, even though he was from the Germanic Frankish tribe, as were the leaders of his dominions. Franks west of the Rhine in time adopted the local Romano-Gallic languages and gave their name to France.

Drawing of Clovis – courtesy of Uncork Champagne Tours

Clovis’ conquered territories; Bretons (northwest of his territories) were named such since they prior lived in the British Isles, but were evicted by the invading Angles and Saxons (who morphed into Anglo-Saxons); Frisians are a distinct ethnicity with their own language in both Germany and the Netherlands; mainland Saxons birthed Germanic dialect spectrum Low Saxon/Low German, difficult to understand for speakers of Central and High German; Belgica was transformed into the modern namesake of Belgium; Burgundians gave their name to a type of edible snails (which one of our blog writers got ill from, so they’ll never eat snails again); Lombards travelled south into northern Italy and assimilated locally; Visigoths and Ostrogoths likewise assimilated – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

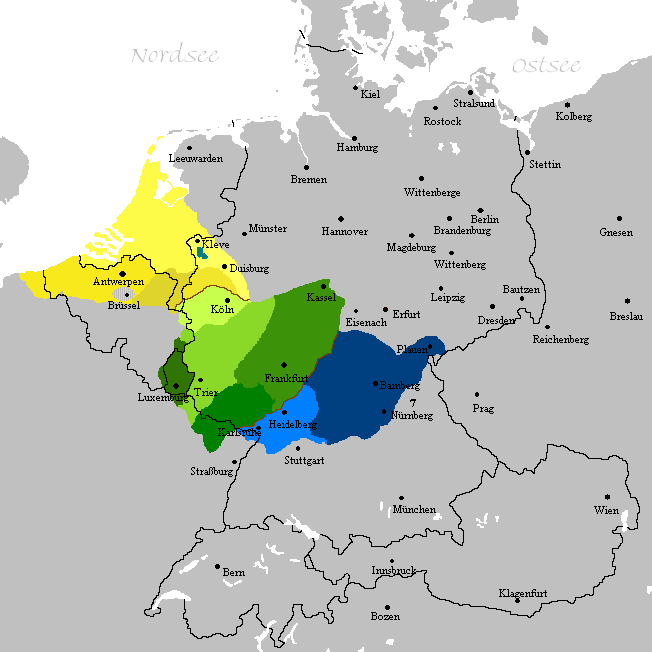

Franconian Dialects across France, Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, and Germany; Dutch (brightest yellow) is lumped in, but is more closely related to eastern adjacent Low Saxon/Low German dialects (YouTube channel LangFocus more or less says LG/LS is a bridge between Standard German and Dutch, while Dutch is a bridge between German and English); Trier is around where our later matrilineage is from (though her surname is LG/LS); green shades within Germany are around where Pennsylvania Dutch and their language originate; and blue shades are where northernmost (High Franconian) High German dialects are (Alemannic and Austro-Bavarian are southward) – courtesy of Simple Wikipedia

Alemannic Classification

The Alemanni’s speech evolved to the modern Alemannic dialects. All of them varyingly differ from Standard German (Hochdeutsch). Their broadest divides are into Swabian, Low Alemannic, and High Alemannic categories. Swabian is spoken in eastern Baden-Wurttemberg and western Bavaria (Castle Neuschwanstein isn’t in “Old Bayern” (traditional) boundaries, but within a part of Swabia annexed to Bavaria). Low Alemannic is spoken in Alsace and much of the rest of Baden-Wurttemberg, including the Schwarzwald/Black Forest. High Alemannic is spoken in Switzerland and Austria’s Vorarlberg.

Local Alemannic spelling and pronunciation beneath each city’s name; “Souabe” is Swabian; Low Alemannic is divided into Rheinish (Rhenans Superieurs) and Lake Constance; High and Highest Alemannic are in Switzerland; not shown is the highest Alemannic dialect, Walser German, slightly above and mostly below the Rhone – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

19th century Castle Neuschwanstein owes more to fairy tale models of castles instead of more authentic medieval ones; the castle is an icon of Bavaria (and Germany), but is in Swabia, a traditionally Alemannic cultural sphere – courtesy of Travel + Leisure

Swabian Jura (alternatively known as the Swabian Alb), which runs through the center of this Alemannic cultural area – courtesy of Komoot

Vosges Mountains, Western Alsace – courtesy of PlanetWare

Ruins of Schloss Hornberg – Castle Hornberg – on left, part of the Schwarzwald town of Hornberg; on the right is the Hornberg hotel, which, in addition to its coziness, contains replicas of medieval German paintings – courtesy of http://www.booking.com

Lauterbrunnen, Canton Bern, Switzerland – courtesy of World of Waterfalls

Vorarlberg, Austria; the lines on the mountain at upper left are avalanche barriers for both solid ground and snow falling and sliding; similar avalanche barriers are found throughout the Alps – courtesy of The Hotel Guru

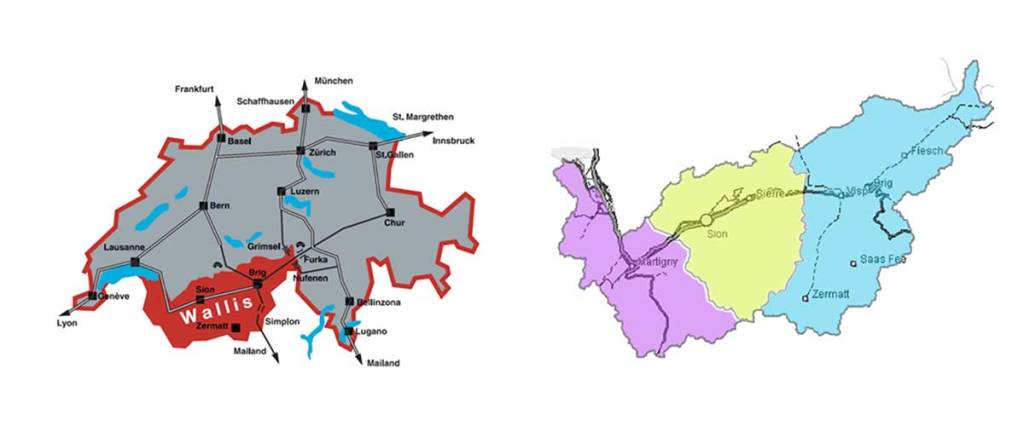

Walser German is the furthest south Alemannic dialect, and perhaps the most obscure. Walser German is located at eastern Valais canton, home (heim?) of the Matterhorn.

Valais (French), or Wallis (German); Zermatt is the village near the Matterhorn; Zermatt, to preserve its air quality, permits only electric vehicles – courtesy of Packed Again

Gornergrat Railway near Zermatt and the Matterhorn – courtesy of Matador Network

An Alemannic colonization of Upper Valais occurred in the 7th century A.D. Fights and peaceful encounters with non-Alemannics occurred over time, to where non-Germanic influences made their way into the Walser dialects. Further Germanic colonies were made in Valais in the 13th and 14th centuries A.D. The Walser-speaking areas were isolated even for Switzerland, thus held onto Medieval High German features which were less obvious or disappeared in other Germanic languages.

A sample of this is (first excerpt courtesy of Wikipedia, second excerpt courtesy of Google Translate of English translation, third excerpt courtesy of Wikipedia):

“Méin oalten atte ischt gsinh van in z’Überlann, un d’oaltun mamma ischt van Éischeme, ischt gsing héi van im Proa. Stévenin ischt gsinh dar pappa, la nonna ischt gsinh des Chamonal. […] D’alpu ischt gsinh aschua van méin oalten pappa. Ich wiss nöit ol z’is heji… Ischt gsinh aschuan d’oaltu, un d’ketschu, gmachut a schian ketschu in z’Überlann. Méin pappa ischt gsinh la déscendance, dschéin pappa, aschuan méin oalten atte, ischt gsinh aschuan doa .. Vitor van z’Überlann. Un té hedder kheen a su, hets amun gleit das méin pappa hetti kheisse amun Vitor. Eer het dschi gwéibut das s’het kheen sekschuvöfzg joar un het kheen zwia wetti das .. zwienu sén gsinh gmannutu un zwianu sén nöit gsinh gmannutu. Dsch’hen génh gweerhut middim un dschi pheebe middim. Un darnoa ischt mu gcheen a wénghjen eina discher wettu” – Walser German; note that as in the rest of Switzerland, dialectal differences are often on a scale as small as village to village

“Mein Großvater kam aus Gaby, meine Großmutter aus Issime, aus dem Weiler Praz. Stévenin war der Vater, die Großmutter kam aus der Familie Chémonal. […] Die Weide [im Bourines-Tal] gehörte wahrscheinlich meinem Großvater. Ich weiß nicht, ob er väterlicherseits war. Sie gehörte meiner Familie, sie hatten ein schönes Haus in Gaby. Victor, mein Vater, stammte aus seiner Linie, sein Vater, mein Großvater, kam von dort drüben… Victor le gabençois. Später bekam er einen Sohn, dem er seinen Namen gab, so dass auch mein Vater Victor hieß. Er heiratete dann mit 56 Jahren und hatte vier Schwestern, zwei von ihnen heirateten und zwei nicht. Sie arbeiteten und lebten immer bei ihm. Später starb eine von ihnen” – Standard German, or Hochdeutsch, rendition of the same sentence

“My grandfather came from Gaby, my grandmother from Issime, from hamlet Praz. Stévenin was the father, the grandmother came from the Chémonal family. […] The pasture [in the Bourines Valley] probably belonged to my grandfather. I don’t know whether he was from my father’s side. It belonged to my family, they had a beautiful house in Gaby. Victor, my father, was from his lineage, his father, my grandfather, came from over there… Victor le gabençois. Later he had a son, to whom he gave his name, so that my father’s name was Victor too. He then got married when he was 56, and he had four sisters, two of them got married and two did not. They always worked and lived with him. Later one of them died” – English translation of original Walser

Alemannic isn’t all there is to German dialects

We hope this page and other sources get you interested in the fascinating array of German dialects.

Dark orange: Frisian; Purple: Low Franconian; Blue: Low German/Low Saxon; Light Yellow: Central German; Dark Yellow: High German – courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References:

- “Alemanni”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Alemanni

- “Alemannic”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Alemannic

- “From Valais-German to Walser-German”. Walser in den Alpen. http://www.walser-alps.eu/dialect